Breaking the Vicious Cycle of Poor Health and Extreme Poverty in Uganda’s Most Overlooked Communities — With Your Help, Wherever You Are.

Health and Poverty: Two Chains that Bind

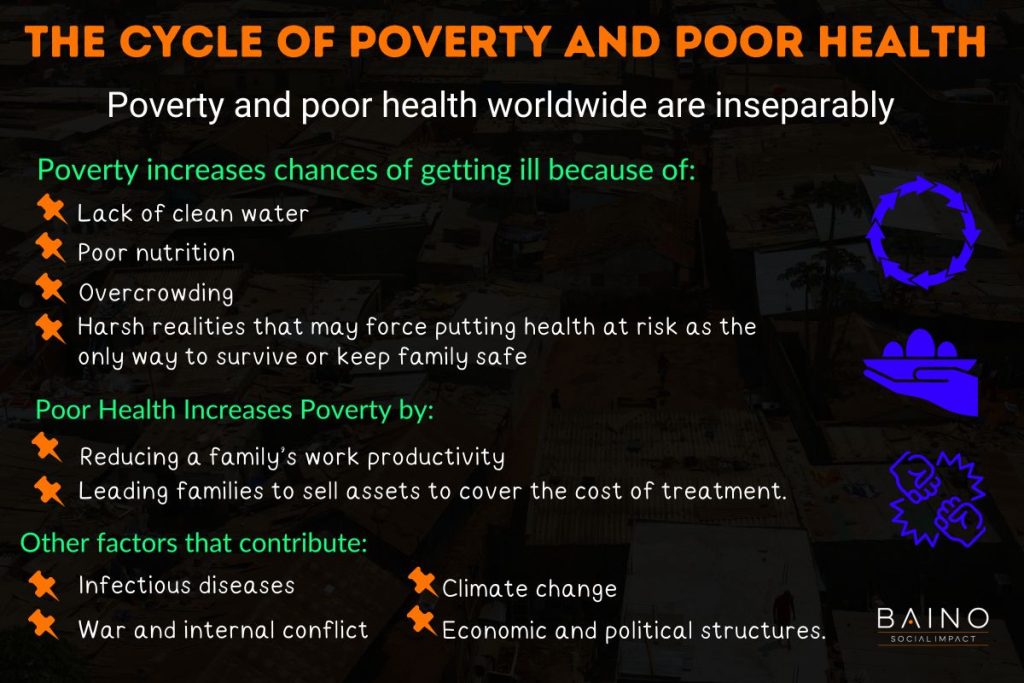

For decades, experts have debated whether deprivation leads to ill health or whether poor health is a precursor to poverty. Today, research confirms both truths: poverty and poor health almost always coexist, forming an unbreakable chain that holds communities down.

Your support today can strengthen healthcare systems, restore dignity, and give children and families a fighting chance to thrive.

Donate now.

In Uganda’s Busoga region, this harsh reality is undeniable. For years, Busoga has faced some of the most severe health challenges in the country’s history.

Today, it continues to battle persistent diseases and systemic neglect that rob its people of dignity, hope, and life itself. This community urgently needs support to gain control over their health and reclaim their future.

Poverty as a Cause of Poor Health

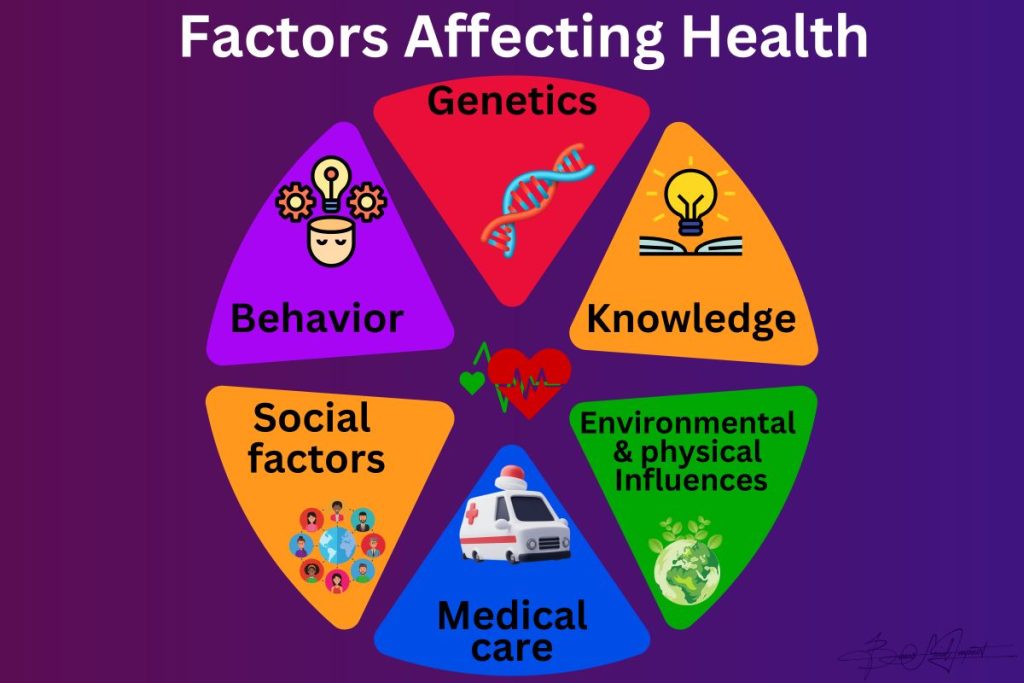

Poverty is a major driver of ill health. It fuels the spread of disease, weakens health services, and slows down population growth management. Improving health and longevity for the poor is not only an ethical imperative – it is a powerful foundation for long-term economic development and the eradication of poverty itself.

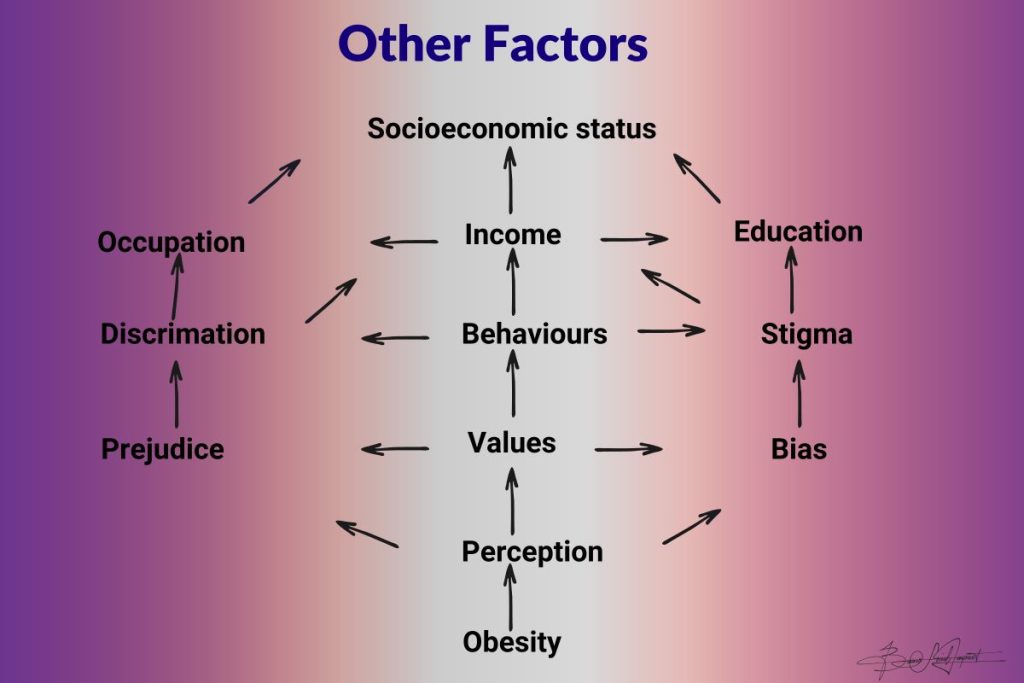

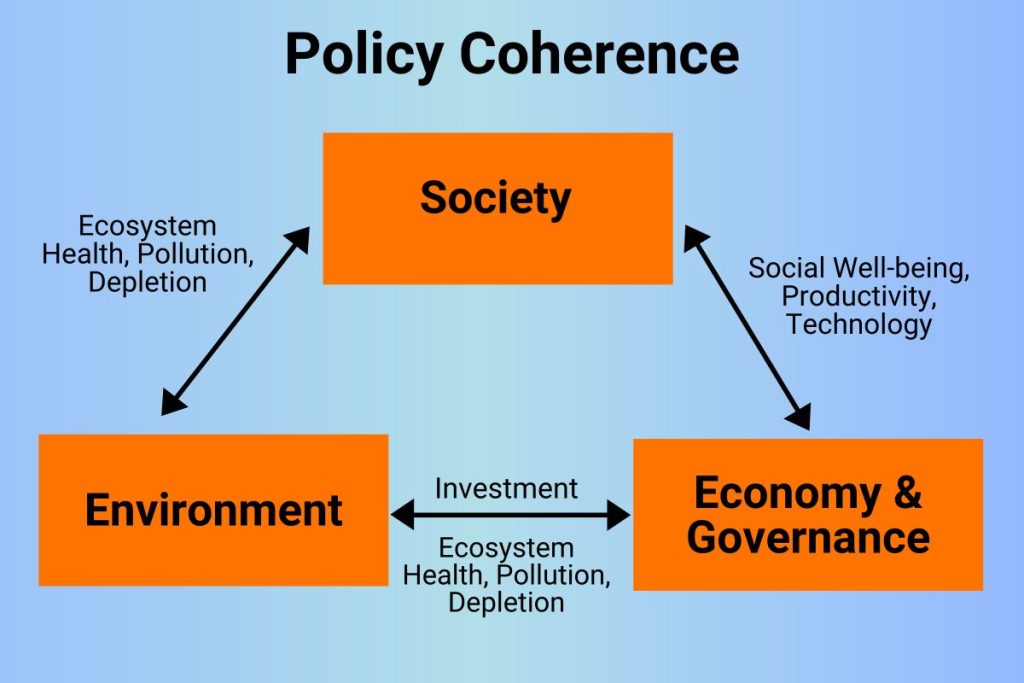

However, poverty is a complex condition rooted in factors that extend far beyond the health sector alone. Eradicating it requires a multisectoral, community-based approach, recognising that health is deeply connected to education, income, environment, and social equity.

Health as a Resource, Not Just an Outcome

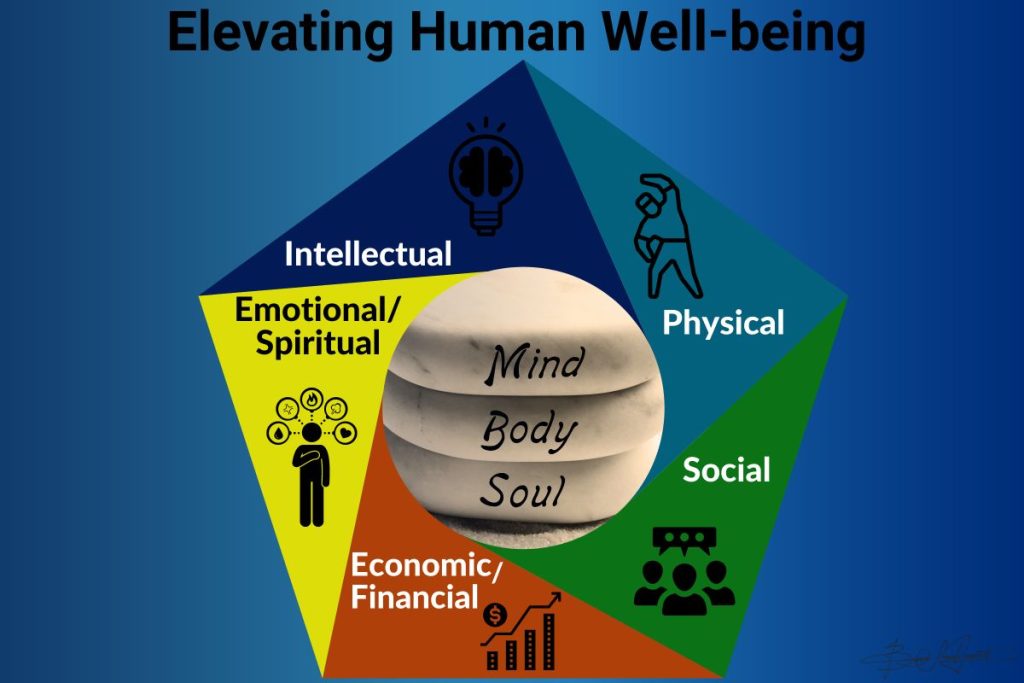

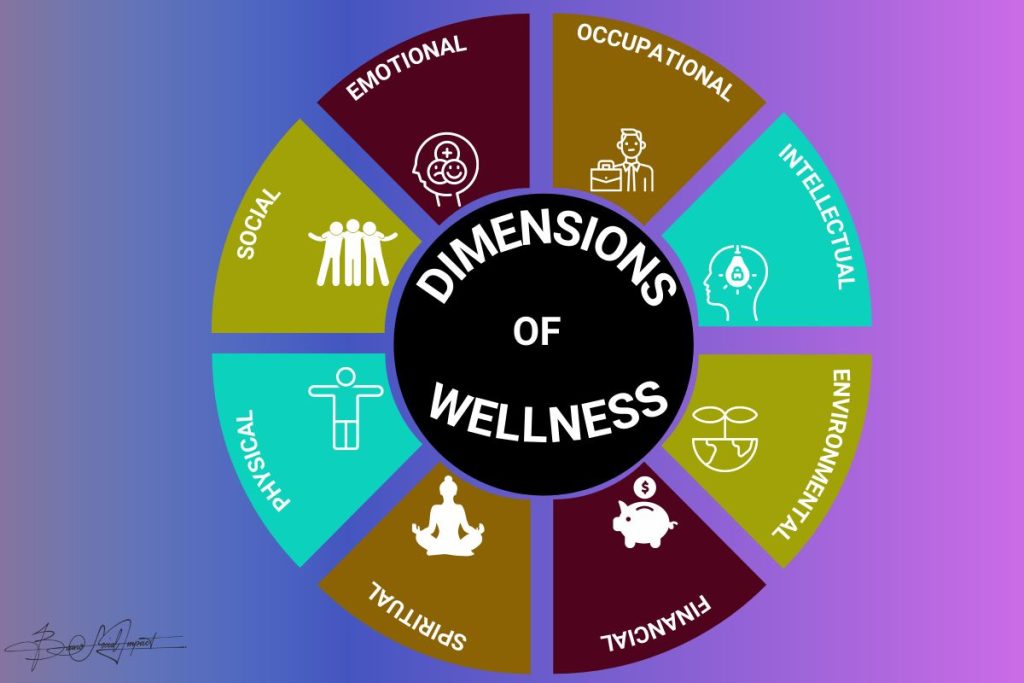

Health is not merely the absence of disease. It is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and a resource for everyday life – enabling individuals to function with meaning, purpose, and dignity in society.

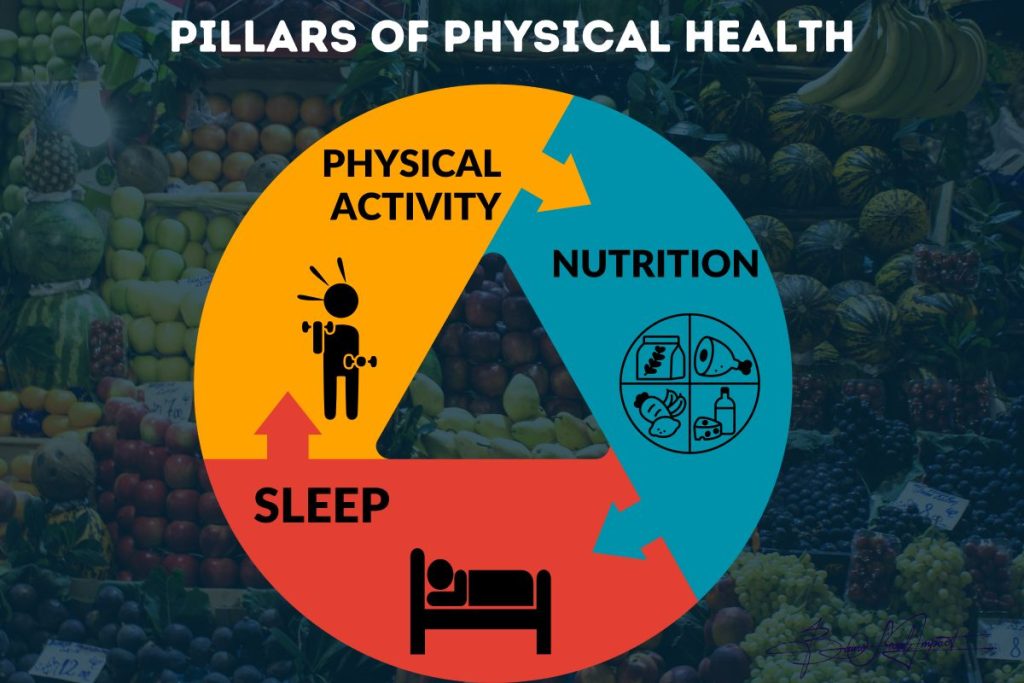

Physical and mental health work together to improve quality of life. While good health doesn’t mean the absence of all ailments, it requires balanced nutrition, clean water, safe housing, healthcare access, and healthy behaviours.

This includes regular exercise, adequate rest, effective hygiene, immunisations, and avoidance of tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drugs.

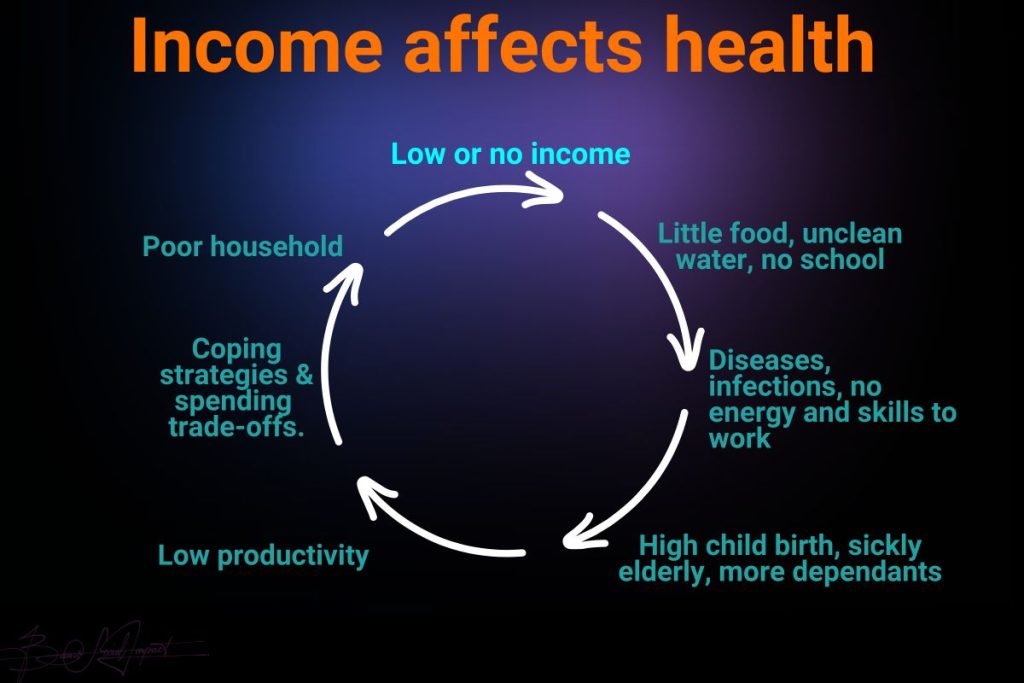

Income and Health: A Powerful Link

Income directly affects health by providing the means to obtain essentials such as food, shelter, warmth, and medical care.

Low income increases exposure to harmful environments, limits the ability to meet basic needs, and reinforces health-damaging behaviours.

This vicious cycle entraps families generation after generation, unless it is broken with strategic, compassionate interventions.

Investing in Health Is Investing in Uganda’s Future

The World Health Organization’s Commission on Macroeconomics and Health is clear: investment in health is a cornerstone of economic development. Without substantial health improvements, developing regions like Busoga remain trapped in poverty’s vicious cycle. But with strategic health interventions, communities can thrive.

Here’s why health matters:

- Higher Labour Productivity: Healthy workers are more productive, earn better wages, and miss fewer days of work. This increases output, strengthens local economies, and improves household incomes.

- Increased Investment: When labour productivity rises and diseases like HIV/AIDS are controlled, both domestic and foreign investors gain confidence, creating jobs and fostering economic growth.

- Greater National Savings: Healthier people save more, live longer, and invest in their futures, building economic resilience across generations.

- Demographic Dividend: Better health and education lower fertility and mortality rates, reducing the burden on working-age adults and enabling societies to progress sustainably.

- Improved Human Capital: Healthy children have stronger cognitive potential. They learn better, drop out less, and become skilled adults who uplift entire communities.

Health Improvements Have Generational Impact

Health investments create powerful intergenerational benefits. Families with access to health care have fewer children, but each child receives better nutrition, education, and care. As a result, these children avoid many of the cognitive and physical impairments linked to early poverty, perform better in school, and grow into healthy, productive adults. They then pass these benefits to their own children, breaking the cycle of poverty once and for all.

This is why your support matters. By investing in health today, you empower entire generations to rise from poverty.

Donate now to transform lives.

A Pro-Poor Health Approach

A Pro-Poor Health Approach: Reaching Those Who Need It Most

A pro-poor health strategy prioritises the well-being of low-income communities by ensuring access to quality public health and personal care services. But it goes beyond clinics and hospitals; it addresses interconnected factors like education, nutrition, water, sanitation, and global trade policies that impact health outcomes.

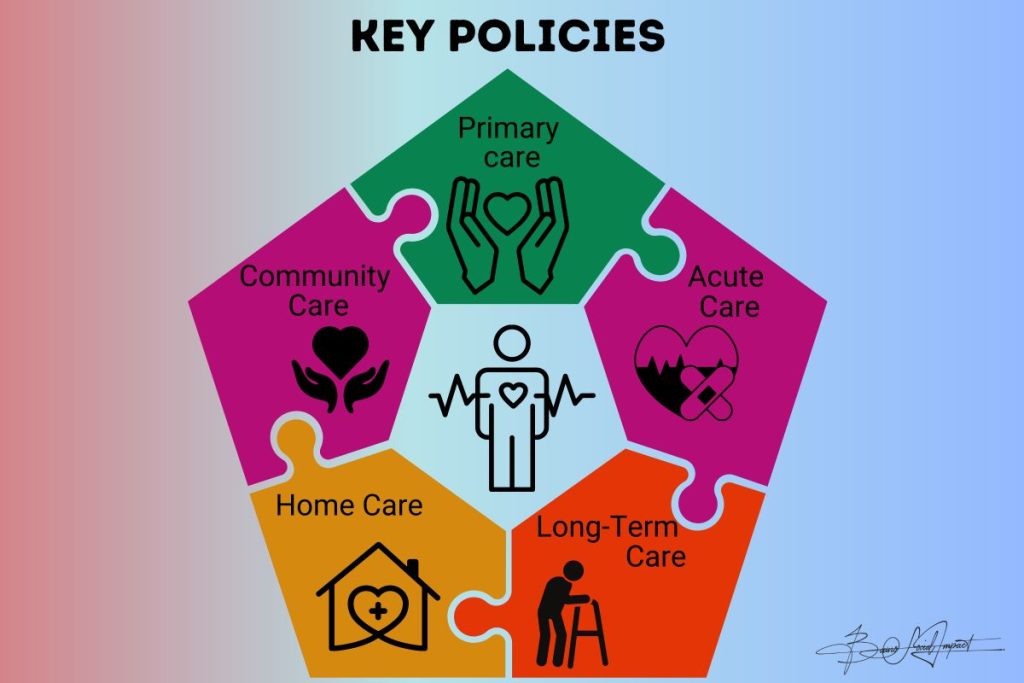

Four Pillars of a Pro-Poor Health Strategy:

- Strengthening Health Systems

Health systems must provide promotive, preventive, curative, and rehabilitative services accessible to all, including women, ethnic minorities, and vulnerable groups. This requires stocking facilities with medical equipment, programs, and personnel while dismantling biases that restrict access.

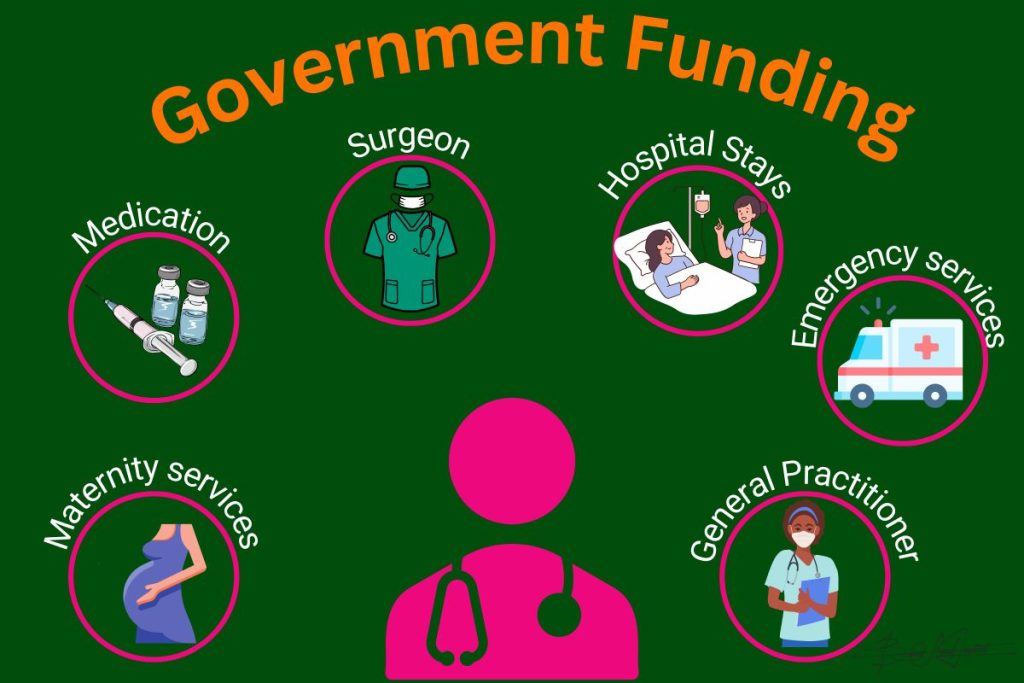

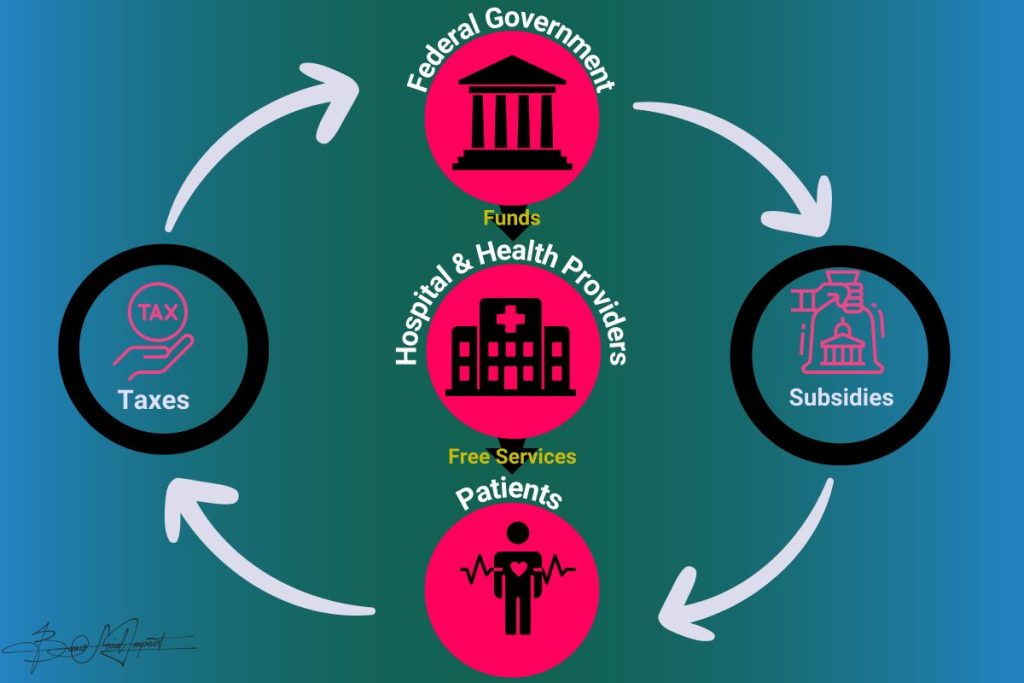

2. Health Financing

Protecting families from the devastating costs of illness is crucial. Health financing strategies must pool risks, subsidise the most vulnerable, and shield them from financial shocks that destroy livelihoods.

3. Integrating Key Policies Beyond Health

Poverty, education, food security, clean water, sanitation, and environmental conditions all shape health. Therefore, national poverty reduction programmes must align policies outside the health sector with pro-poor health objectives to ensure every intervention strengthens human well-being.

4. Promoting Global Policy Coherence

Globalisation brings both risks and opportunities for health. International action – from disease prevention conventions to fair trade policies – must complement local efforts to protect and empower the poor.

When health is prioritised, poverty loses its grip. Your commitment can make this vision a reality. Support our mission to deliver life-saving health interventions to Uganda’s most neglected communities today.

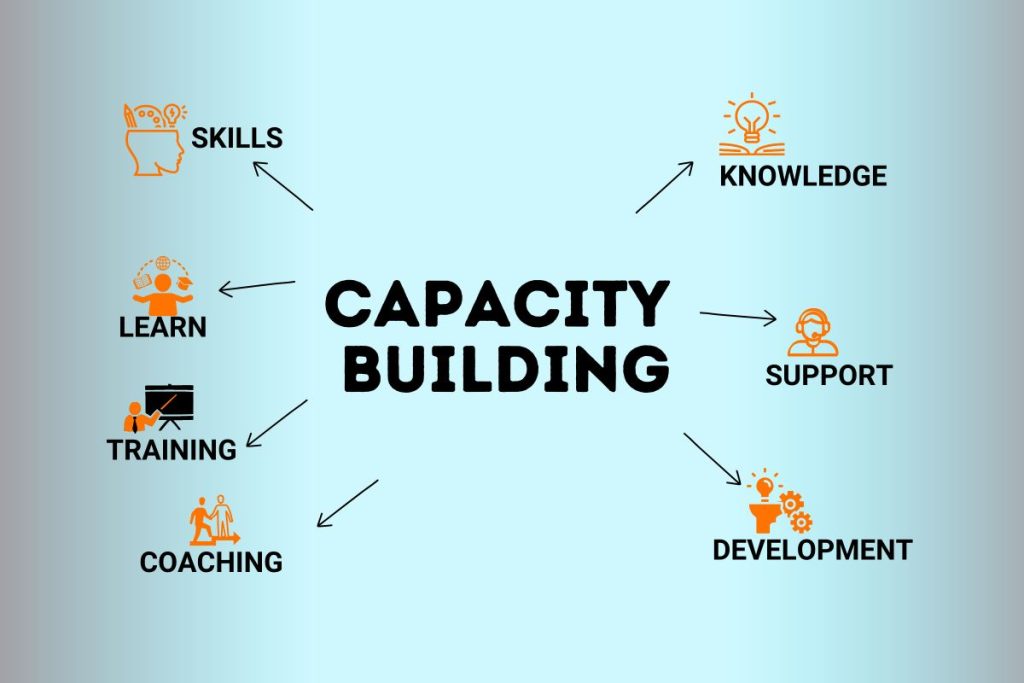

Embracing Innovative Health Interventions

When we think about health interventions, it’s easy to view financial resources as the only cornerstone for success. But while funding is crucial, solutions built by communities themselves often generate the most lasting results. These grassroots interventions may not make it to scientific journals, but they spread organically, transforming health at individual, communal, and national levels. Empowering communities to create solutions for their own health challenges is a strategy that cannot be ignored.

Health financing

Today, health stands higher than ever on the global agenda. Nations worldwide acknowledge that the highest attainable standard of health is a fundamental human right – regardless of race, religion, politics, or economic status. International commitments, like the UN Millennium Development Goals, emphasise reducing child mortality, maternal deaths, and the spread of HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis.

Preserving Health

Preserving Health and Cultivating Lifelong Wellness

The best approach to health is proactive: preserving it through a healthful lifestyle before sickness strikes. Wellness is the ongoing journey towards our fullest physical, psychological, social, spiritual, and economic potential. It means fulfilling our roles in family, community, and society with purpose.

Maintaining wellness is a lifelong daily commitment – eating a nutritious diet, engaging in regular exercise, undergoing disease screenings, connecting with and caring for others, and nurturing a positive outlook. While diseases cannot always be prevented, each individual deserves the resources and opportunities to achieve their personal definition of peak health.

Yet, a lack of health resources remains a formidable barrier in places like Busoga. National health spending often falls short of meeting even the bare minimum requirements for the poorest communities. Budgets must reflect the urgency of these challenges, ensuring enough funding for vaccines, essential medicines, adequate staffing, and well-equipped facilities. Far too often, resources intended for primary health care and district hospitals are diverted elsewhere, leaving the most vulnerable behind.

“Health is not just a medical concern—it’s a cornerstone of dignity, development, and equality. As the world recognizes health as a fundamental human right, we must ensure that no one is left behind—not because of where they were born, what they believe, or how little they earn. A healthier Uganda begins when we commit to closing these gaps—together.”

Global commitments like the Millennium Development Goals remind us that health is both a moral imperative and a measurable mission. From reducing child and maternal mortality to halting the spread of HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis, the world has drawn a line: poverty should never decide who lives or dies. Now more than ever, we must turn these goals into action—especially for the poorest, whose lives depend on it.

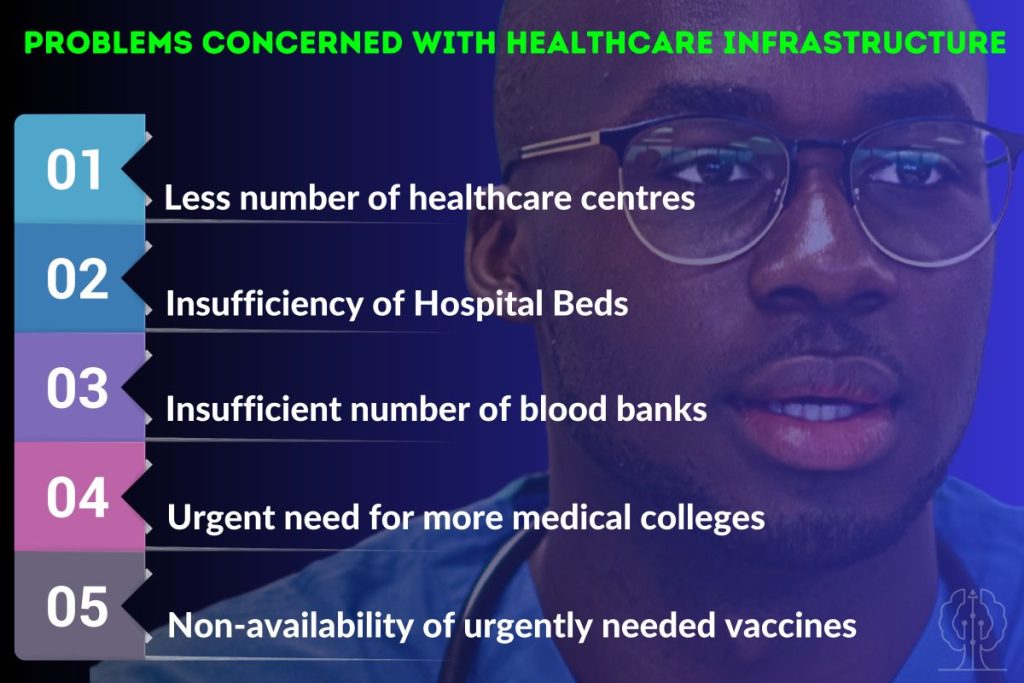

Building Infrastructure for Health

Building Infrastructure and Partnerships for Health

To meet the basic health needs of Busoga’s people, robust health infrastructure and targeted interventions are non-negotiable. Development agencies must engage in constructive dialogue with government bodies to ensure resources are allocated effectively to benefit the poor and socially vulnerable. Increased funding should come from public, private, domestic, and international sources, including global health initiatives.

Without significant external support and the strengthening of health systems, Busoga will remain unable to achieve pro-poor health objectives. Change requires all stakeholders – donors, policymakers, community leaders, and development agencies – to work in unison.

Community wellness begins not in hospitals, but in the quiet agreements we make—to listen more, to share what little we have, to carry one another through the ordinary storms of life. True wellness is not just the absence of illness, but the presence of belonging, dignity, and shared purpose.

Primary healthcare in underserved communities is not just about clinics or medicine—it’s about trust arriving on foot, compassion wearing the face of a neighbor, and prevention whispered in local languages long before pain becomes crisis. It’s where healing begins with listening, and health grows from the roots of dignity, proximity, and everyday courage.

In impoverished communities, health infrastructure is more than bricks and beds—it is the silent backbone of hope. It is the light that stays on through childbirth, the clean water that stops disease before it starts, the safe roof where care meets trust. Without it, illness travels fast and healing stands still. With it, a future becomes possible.

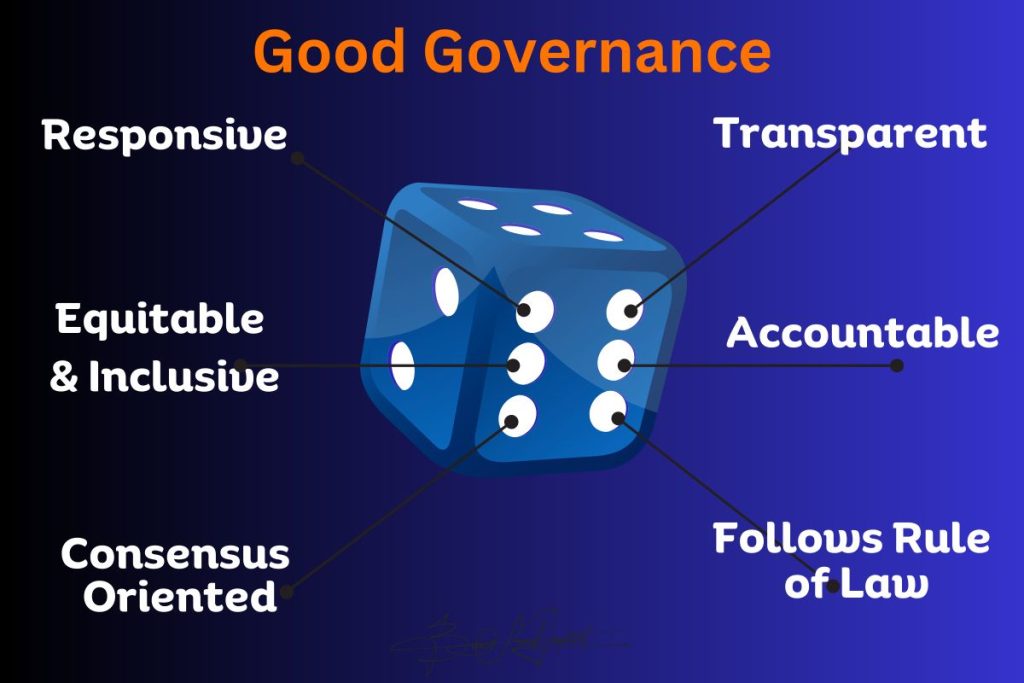

Accountability, Governance, and Empowerment

For lasting health improvements, accountability, monitoring, and evaluation must be prioritised. Transparent governance creates fair legal, policy, and regulatory frameworks, ensures effective and accountable government agencies, and enables the participation of the poor in decision-making. Only with good governance can poverty reduction strategies and health sector programmes deliver their promised impact.

Development agencies are more likely to support pro-poor health objectives when there is visible political, social, and economic commitment. Managing resources effectively and inviting stakeholders to participate in planning and delivery not only boosts credibility but also inspires generosity and active involvement from all partners.

A Call to True Transformation

The living conditions in Busoga demand a transformation that goes beyond health – it requires political and economic restructuring, fiscal reforms, and democratic participation. Coordinating all efforts magnifies impact, aligns aid with national strategies, and ensures interventions support the region’s broader poverty reduction goals.

Health is not merely the absence of disease; it is the foundation of human dignity, productivity, and hope. Partner with us today to strengthen health systems, empower communities, and build a future where every person in Uganda can thrive in good health.

Donate now to transform lives.