Education is the process of facilitating learning - acquiring awareness.

Access to quality education for knowledge and life skills is the most famous tool for creating lasting changes.

Education, the process of facilitating learning or acquiring knowledge, skills, values, morals, habits, and personal development, is a tool that every developed society has applied to attain all forms of admiration. It is the sharpest tool in fighting and conquering poverty and all its other forms.

Education is the pillar of strength of all forms of development ever achieved—and its methods may include teaching, training, storytelling, discussion and directed research.

An Educated Person

The hallmark of a truly educated person is actual development.

To be educated is to possess the ability to formulate serious questions: to constructively and independently inquire and create without being constrained by external controls. Put another way; it is the ability to reason analytically and think critically in exercising good judgement.

An educated person has invested efforts to develop all the faculties of their mind. As a result, they know how to acquire knowledge and skills and make productive use of those values to obtain anything they want, or its equivalent, without violating the rights of others.

In other words, this kind of education that strengthens one’s inbuilt qualities calls for being innovative and adaptable to changes. All these traits of an educated person need to be kindled and nurtured right from childhood.

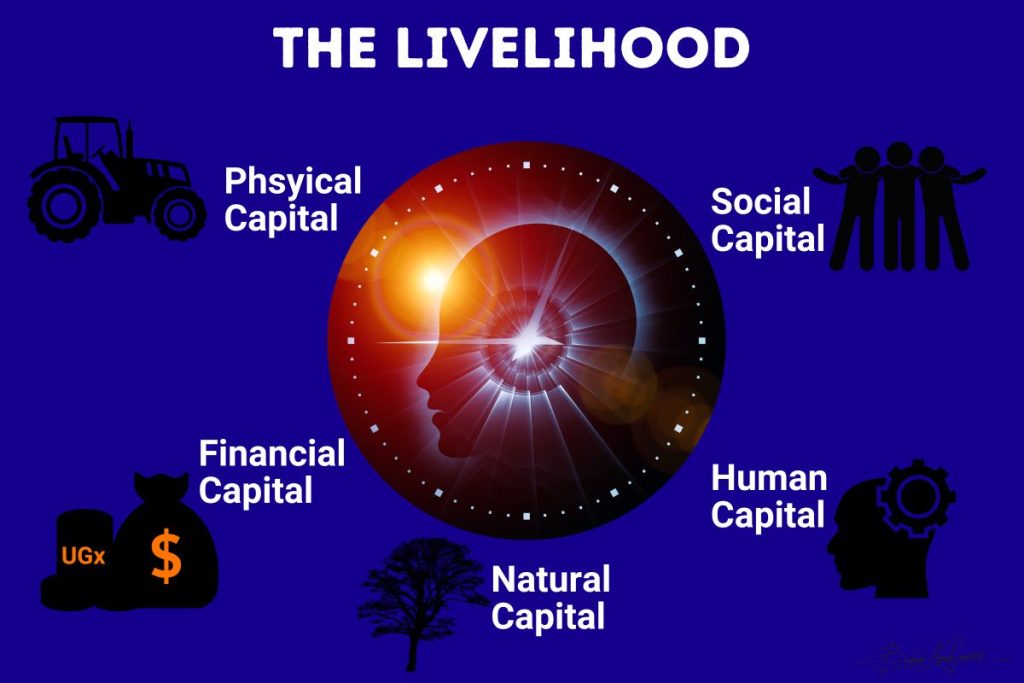

Poverty is inversely and inextricably linked to education, and this correlation is cyclical. The more education a person has, the more skills and knowledge they can likely pull together to increase productivity and diversify their sources of income. And as expected, educated people are also more resilient to change in life’s economic, environmental and personal turmoil.

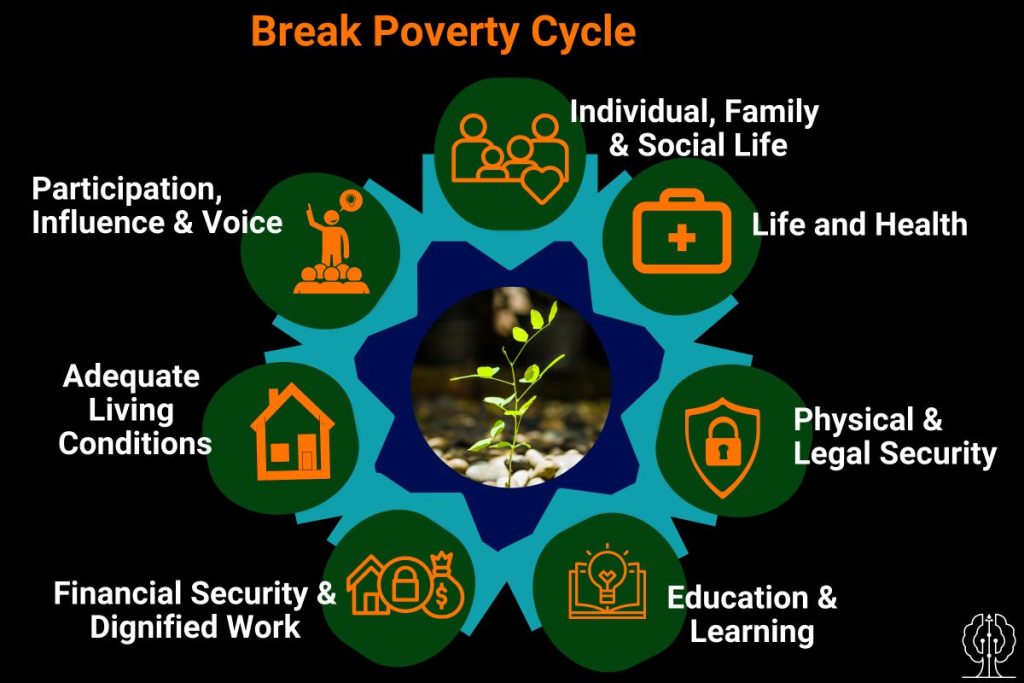

Break the Poverty Cycle

While the repercussions of poverty are multifaceted and take many forms, quality education is a critical tool for escaping and breaking the cycle, no matter how complex the process is.

The less money and resources a person has, the less likely they are to receive a quality education. The less likely they are to receive a quality education, the fewer resources they can forge, create and accumulate. The pattern continues up to the point of giving up all efforts to escape the scourge: the cycle.

Poverty has a powerful, lasting negative impact on individuals and societies, such that only quality education for all can meaningfully contribute to attaining the international goals of sustainable development to break that cyclic pattern of doom.

The irony is that poor people are less likely to go to school for varying reasons. When they find themselves in school, they are less likely to get quality and meaningful education. As pointed out, this has tragic consequences and perpetuates intergenerational poverty: the poor stay poor. Therefore, there is a need to strategically wage war against poverty to have any chance of escaping that cage of rack and ruin.

Poor Education Condition

As far as education is concerned, Busoga region finds itself in a treacherous position.

Many children don’t attend school; the few who attend are dropping out at a terrifying speed, and yet the few existing schools in the region are of poor quality, to put it mildly, with no scholastic material to begin with or qualified educators to guide them.

Children are graduating from the primary grade level without the basic skills which will allow them to continue their education at the secondary level. Some of those graduates can hardly write their names. It’s appalling.

According to the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS), Busoga sub-region has the highest number of children (aged 6–13) in employment (31%) compared to less than one per cent in the central region (child labour). This has come with low enrolment rates and high dropout rates at both the universal primary and secondary education levels.

In 2019, the Ministry of Education statistics showed that Busoga region had the highest rate of teenage pregnancies, with early and forced marriages in the country reported to be at 42%.

Regarding distance, 47% of communities showed that the government secondary school outside their local council (LCI) was at least five or more kilometres from the village centre. Over 41% of communities in Busoga reported that the closest government primary schools were outside their LCI. Only four per cent of communities reported having at least one government secondary school within their LCI.

When the government recognised in 1997 that poverty, illiteracy, and sickness were the principal impediments to human socioeconomic growth, it implemented free primary education (UPE) to address these issues.

The nation experienced an overall increase in school enrolment, and relevant support was provided per available resources. As a result, there was a general decrease in child labour and reduced poverty. Immediately, a sense of hope was created, and songs praising the UPE were composed.

Overall, poverty and child labour were significantly reduced. The nation was immediately filled with hope, and in appreciation, songs praising UPE were composed.

However, due to the nation’s political climate and numerous other variables, the distribution of the allocated resources to all parts of the country was far from even.

Politics in the country is a product. It’s about who has it, how it is used, and how allies use it to benefit their motives. Politics is about power and control. It’s a powerful string that commands the direction of all resources. Once you are not in, you are out. Busoga region has always been ‘out’. It faced the consequences, and the conditions were and are still evident to the naked eye. As a result, the hopes and promises of free education did not materialise in Busoga.

There was a complete lack of structural development, as well as other assistance needed to launch and sustain such a programme. Furthermore, the early enrollment suffocated the few existing schools. It put an enormous strain on existing physical and human resources. As a result, the problem became worse instead of being addressed. Overcrowding in schools severely hampered the substance of learning.

The region saw the departure of qualified teachers from Busoga to neighbouring regions that were getting the program’s promised support and funding.

When it became apparent that school-going-age children were not receiving any actual learning, families started losing confidence in the entire scheme. After all, the ‘free’ education was not necessarily ‘free’ or cheap, as stated, given the direct and indirect costs parents were expected to pay.

To several low-income families, it made more economic sense to send their children to work and for the girls to get married, reducing the cost of their upkeep on family finances.

This, in turn, would jeopardise the region’s expected economic empowerment of families through the UPE programme.

Financially able parents resorted to withdrawing their children from public schools and enrolling them in private ones. They left the substandard and strained education arrangements to low-income families, thereby perpetuating the cycle of poverty, as learning outcomes in the public schools would fail to help transition learners to higher education and, ultimately, to meaningful employment opportunities.

Learners with disabilities have also been neglected and primarily school-excluded. As a result, they are among those that live in dire socioeconomic circumstances due to the lack of government support and lack of employment. Most do not transition to higher education because of these other constraining factors in the financial and social fields.

The need for improved formative assessment and placement of learners with disabilities (LWDs) is a topic that warrants attention.

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected schooling throughout the world, but the Busoga region appears to have been devastated the most. The consequences are severe, particularly in children’s education.

Aside from the current problems, the impacts will likely linger long.

These are the current circumstances in the Busoga region.

Value of Education

However, the failure to properly execute UPE is not a reflection of the failure of education to uplift masses from limited circumstances.

Education is critical for escaping persistent poverty, but it cannot deliver on that promise in such chaotic and apathetic circumstances.

Education, if executed rightly, is undoubtedly the key to ending extreme poverty in the Busoga region because it can unleash a wave of development that can change the direction of people, communities, nations and the future of humanity.

Quality education is truly empowering, and it has to be equally provided for all boys and girls, and all interested women and men, all the time, for life. Research shows that each additional year of schooling can increase a household’s income by at least 10%.

A quality and well-coordinated education system can effectively respond to a country’s social, economic and political objectives.

It has consistently contributed to worthwhile economic progress elsewhere, most notably through enhancing labour force efficiency, developing better technologies, and improving and developing better products and services.

Quality Education Sustains Economic Growth

While economic growth does not automatically reduce poverty, without it, sustained poverty reduction is not possible. It’s this economic growth that can be translated into higher, well-distributed incomes. As a result, poverty levels in households and communities can be reduced.

Increased access to education combats the underlying structures of poverty. Acquired basic skills such as reading, writing and numeracy have a documented positive effect on the incomes of marginalised populations. It increases the rate of return on the economy.

A newly published paper by UNESCO also reported that;

- Education is critical in escaping chronic poverty and preventing the transmission of poverty among generations.

- The rate of return is higher in low-income countries than in high-income countries.

- Primary education has a higher rate of return than secondary education.

- Education enables those in paid formal employment to earn higher wages. It also said that one year of education is associated with a 10% wage increase.

Education also changes structures in food security.

A study from 1980 that is still influential today analysed the effects of primary education on agricultural production in 13 countries. It found that the average annual gain of output associated with four years of schooling was 8.7%.

Therefore, investing in education that provides children and youths with relevant theoretical and practical skills is essential.

Education Makes Children Healthier

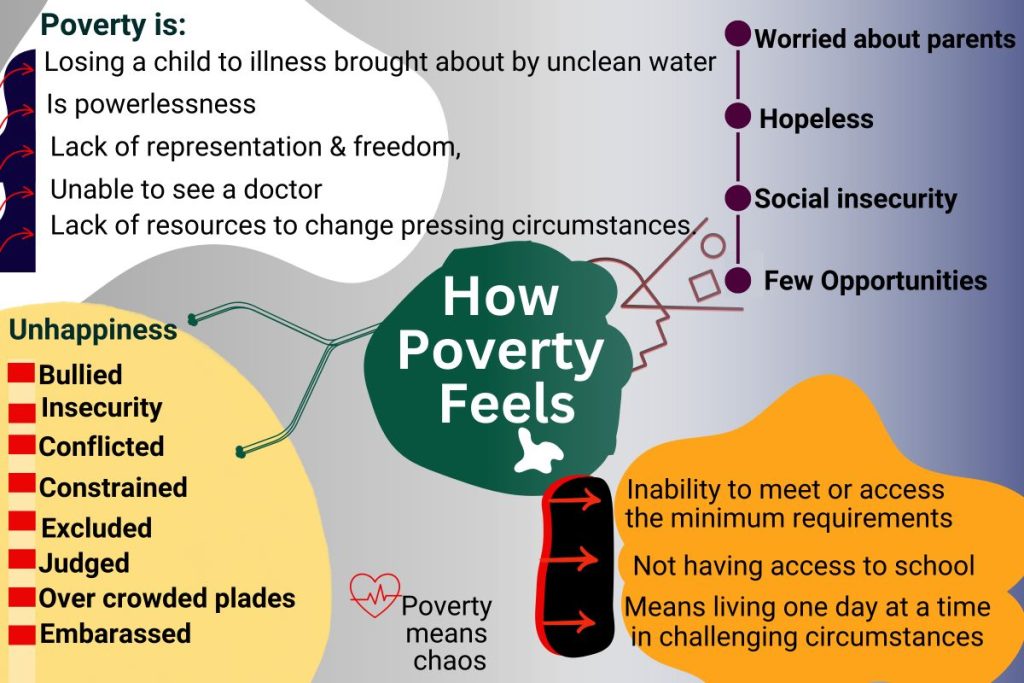

The link between education, health and nutrition is obvious. Although food insecurity and poor nutrition are primarily shaped by poverty and unequal distribution of resources, insufficient knowledge of production methods and nutritional facts share the blame. Children with poor health or who are hungry will not happily attend school—and when they do, their performance in school work is affected.

Many children in the Busoga region face severe nutritional and cognitive deficits from the beginning of life. Estimates suggest that up to one-eighth of all children are born malnourished and that 47 per cent of children in low-income communities continue to be malnourished up to the age of five. Early malnutrition weakens children’s physical and cognitive potential, including their non-cognitive traits, such as motivation and persistence.

Through primary education, marginalised people can learn more about health and better protect themselves and their children from diseases. A child with a mother who can read is 50% more likely to live past their fifth birthday.

The level of health among children and young people improves if their parents have had an education. This increases their likelihood of receiving and benefiting from an education. Improvements in one area reinforce several others.

For girls, the effect of education is powerful. If all women in poor countries completed primary education, child mortality would drop by a sixth. It would be cut in half if they all had a secondary education. Education can prevent maternal mortality by helping women recognise danger signs, seek care and ensure trained health workers are present at births.

One of UNESCO’s mantras is “Girls’ education saves millions of lives”.

Educating girls is also a crucial factor in bringing about lower birth rates. In sub-Saharan Africa, women with no education have 6.7 births on average. The figure falls to 5.8 births for women with primary education and to 3.9 for women with secondary education.

Many of the marginalised families in Busoga region continue to belong to the ever-dwindling income bracket, with lower rates of life expectancy and higher incidences of health problems—including high maternal mortality rates—and they are more poorly nourished than the rest of the population. But despite all these struggles, quality education promises a powerful solution that the region needs. We must rally behind and embrace this service.

In this renewed regional effort to achieve the quality of life, relevant education for all is a powerful tool that can revive the role of education in fighting poverty, creating jobs, fostering business development, improving health and nutrition, and promoting gender equality, peace and democracy.