The power of the community to create health and wealth is far greater than life itself.

Several names are used to describe public participation in policy-making, decision-making, and problem-solving within the challenges they face. It is sometimes called citizen engagement, citizen involvement, community-based decision-making, community-based governance, community policing and neighbourhood-based decision-making.

Whatever term or wording best suits the agenda, public participation is the involvement of people in the process who seek to solve the problems they face or the process of making and applying those decisions to change the current circumstances.

Although it may appear challenging to involve people experiencing poverty in every step of policy-making, they must be a part of the process that proposes a solution to the challenges they encounter.

The neglect or denial of engaging local members, especially the impoverished, in designing and implementing policies or solutions to their challenges leads to social exclusion.

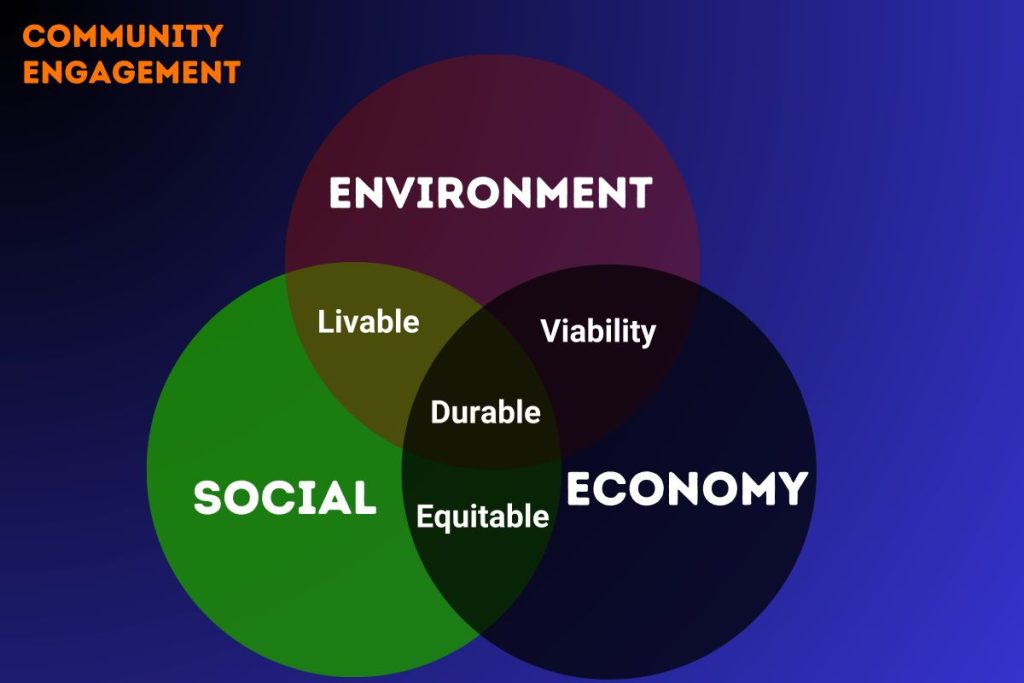

Social exclusion is a complex and multi-dimensional progression. It involves the lack or denial of resources, rights, goods and services and the inability to participate in the normal relationships and activities available to most people in a society, whether in economic, social, cultural or political arenas.

Benefits of Community Engagement

Involving the public has practical, philosophical and ethical benefits.

The underprivileged, more than others, are confronted with the complexity of our society. They experience exclusion more than other citizens because they do not have, or have less access to, other alternatives and socially accepted channels that allow them to exercise their rights or voice their concerns in ways that can be heard and acted upon.

Paying attention to the public’s ideas, suggestions, values, and most pressing issues results in responsive self-governance.

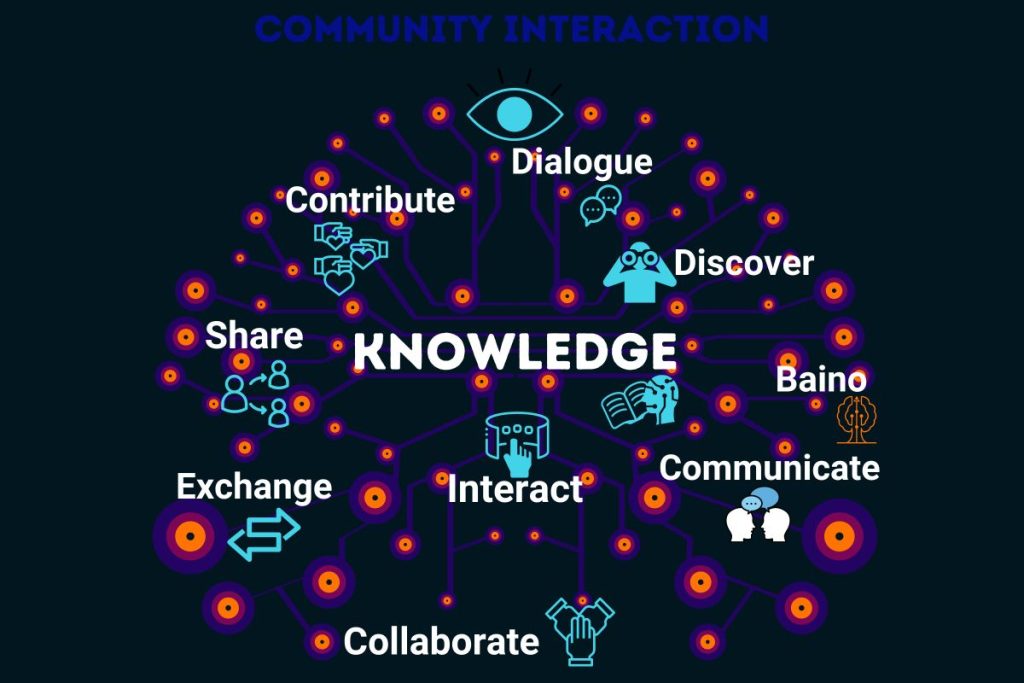

Citizen engagement emphasises the sharing of information and experiences. It’s an approach that can lead to informed decision-making and more robust solutions to problems. It also shows transparency and mutual respect between authority figures and community members. It is appropriate at all stages of the policy development process. It serves to infuse community values and priorities throughout the policy process iteratively.

Still, the citizen engagement approach proposes genuine dialogue and reasoned deliberation to generate new and innovative ideas. And in the processes, members represent themselves as individuals and a general community.

Not only does the participation of the impoverished in policy-making imply their recognition as fully-fledged citizens capable of contributing to the development of society, but it also contributes to the design of more effective policies against poverty and social exclusion.

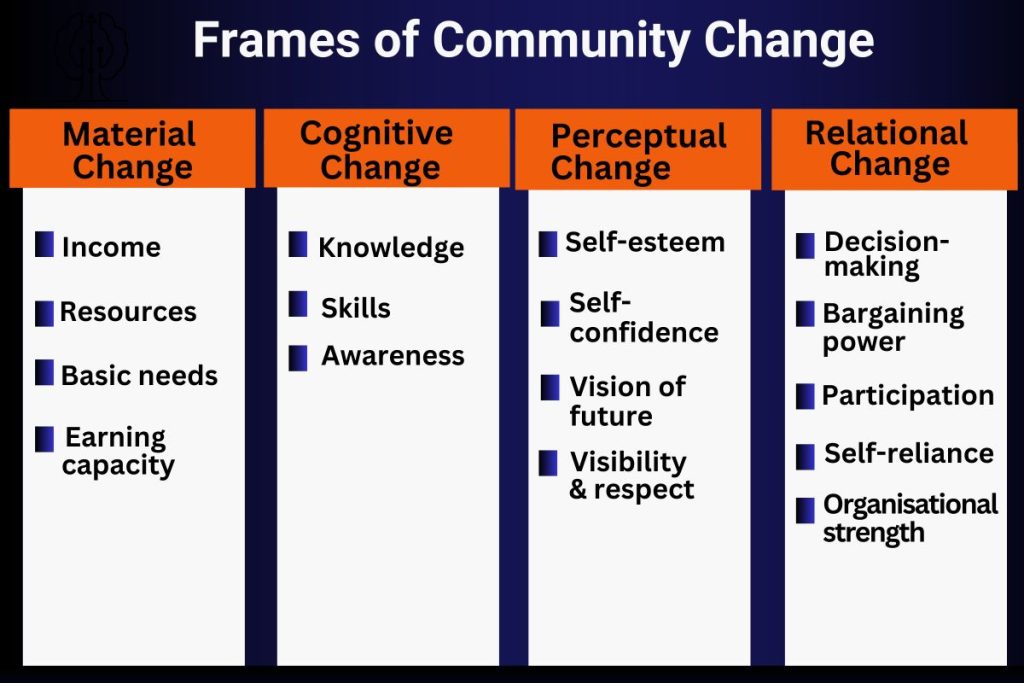

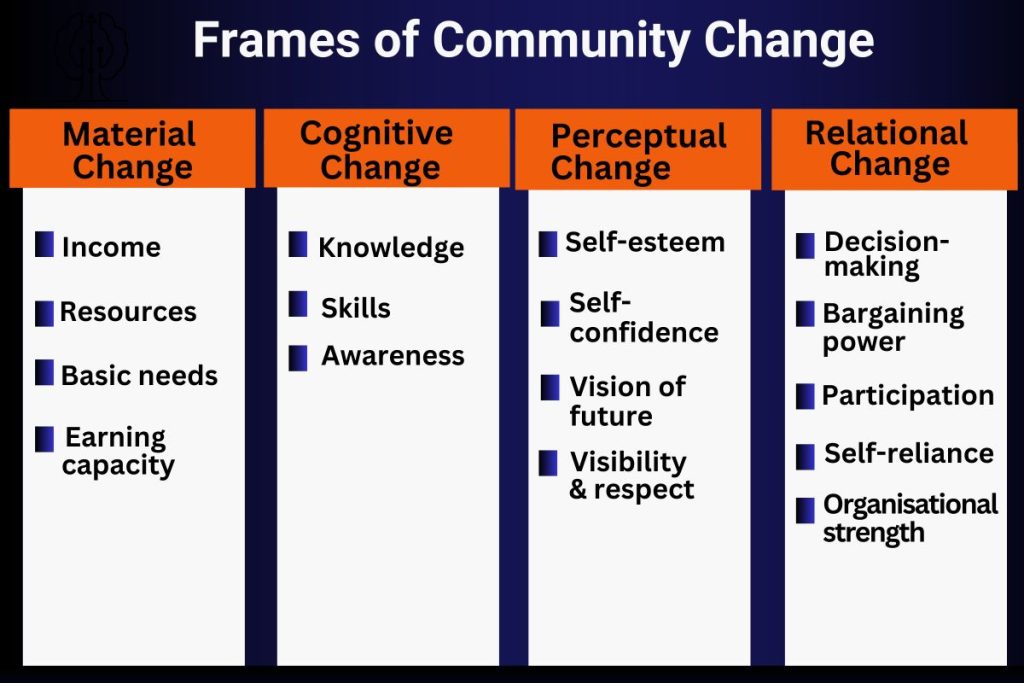

Participation, therefore, implies respect and the recognition that people are competent in all aspects of their personal and social life and that once given the tools and the required support, they can get themselves out of unpleasant social conditions. This competence is not static. It takes shape based on multiple (sometimes contradictory) experiences and interpretations. This is true for all citizens.

Decisions made through community-based processes are more durable and last longer if there is real citizen buy-in on the front end.

If you can get people involved in the problem from the start rather than just coming up with answers, you will create a sense of ownership for both the problem and the solution.

And once they develop the skills to be a part of the solution and what it takes to execute those solutions, they can transfer that knowledge to other pressing issues. It is a sustainable approach.

It is much easier to align the public participation strategy with the intended goal when governing boards, community groups, and organisations are better informed and solutions more strongly address community concerns, in which the community members are well versed.

Clear communication about the purpose of the projects and how they relate to a larger objective can get passed on by involving all stakeholders, especially the proposed beneficiaries. Most especially in communities where trust is an issue, this approach can help forge a level of legitimacy, which is very important.

More information

Better results occur when all stakeholders and decision-makers have access to information. Public involvement brings more details to the final decision, including scientific or technical knowledge, knowledge about the context where decisions are implemented, institutions involved, history and personalities. The nuances and details the public can present can make the difference between a good and a poor decision.

More perspectives

Additional perspectives expand options and enhance the value of the ultimate decision. The more views gathered in a decision, the more likely the final choice will meet the most needs and address the most concerns possible.

Increased mutual understanding

Public involvement provides a platform enabling decision-makers and stakeholders to learn about each other’s concerns and points of view. The discussions broaden the knowledge base, contributing to the final decision.

Involving the public offers a chance to access free consultation from the local members of the society. Local members can assist in identifying critical but unseen obstacles that must be resolved before moving forward.

And in sharing such information, members gain a deeper understanding of their society and how it works. They can then find means and ways to link their personal experiences with modern and researched available social structures.

This approach is one of the modern ways to build better and deeper relationships, manage conflicts effectively, build a coalition of support and stand a high chance of delivering a successful community project.

Challenges to Community Engagement

While it is true that local government is likely to be closer to the individual citizen than leadership at the national level, it’s also true that local citizens are usually not involved in almost all forms of decision-making policies that affect their lives—at all levels of government.

In Busoga region, it has not been a widely common practice of municipal leaders to engage local actors in decision-making processes in almost all impact areas.

They have yet to be involved in the planning, implementing, or evaluating programmes, including those yet implemented in their homes. Local decision-makers, welfare professionals and other officials are not accustomed to this practice.

The reasons for this may vary, but;

Capacity to manage public participation

Local decision-makers may be willing to invite and engage the local people to participate, but they may need to gain the knowledge and skills to organise public participation effectively. Local decision-makers often resort to the distant form of involvement called the ‘classical’ approach. Usually, they provide written comments on printed documents, oral reactions in consultative meetings, and comments on maps showing plans for the development of a community and leave it at that.

The challenge is that many citizens, starting with the underprivileged, are unfamiliar with these ways of working or getting things done. In addition, the language and terms often used in such documents are outside the practical daily challenges they face. This creates a gap between the proposed solution and the actual problem.

These differences in approaches to problem-solving between local decision-makers and the poorest members of the community undermine participation. Decision-makers often think of distinct “policy fields”, while for most citizens, particularly the poverty stricken, experiences and problems are contextually interrelated. Consequently, negative experiences with inclusive participation may lead local officials to take this difference in logic and tempo as an excuse for excluding the challenged members of the society from local decision-making processes.

All actors (local welfare actors, organisations and inhabitants) need information about the objectives, the methods and the channels through which to participate, and about the future impact and feedback of their participation. Such key pointers of information help everyone to formulate reasonable expectations, and they are more likely to share their support as they are motivated by the bigger picture.

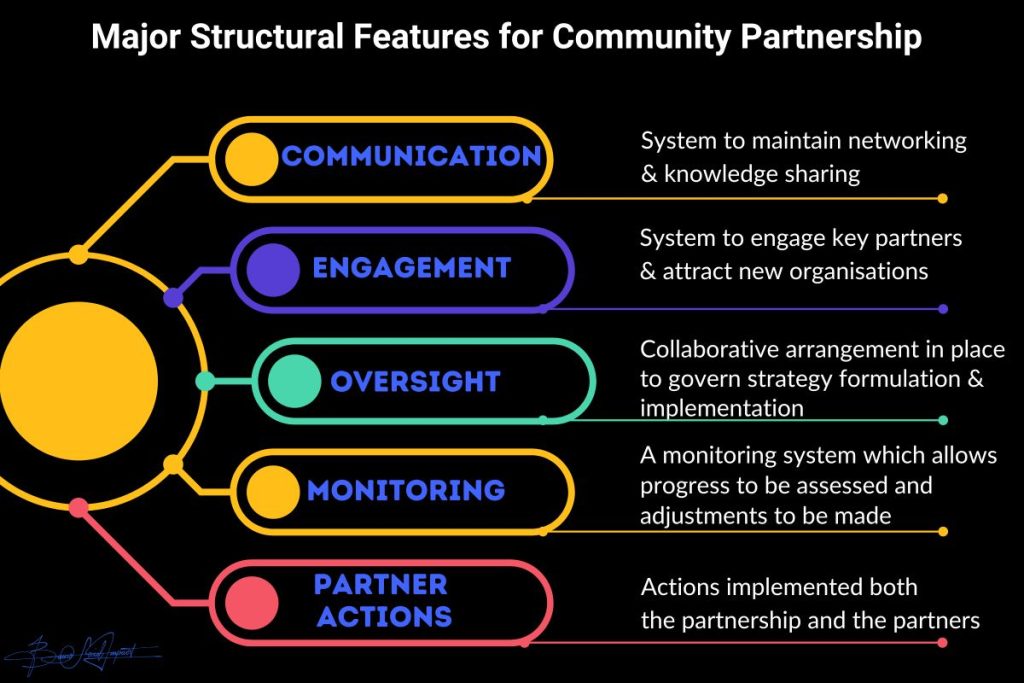

Develop Partnership

Local decision-makers must recognise that all actors are indispensable partners – just as any other welfare organisations and associations representing the intended services. Merely requesting an opinion from an unprivileged member is not good enough. It’s a sign of being noncommittal. The approach of joint analysis of a problem and the formulation of solutions differs from mere consultation.

Participation should not be considered simply as a means to solve problems but rather as a necessary part of the development process and the implementation and evaluation of local programmes.

It doesn’t make sense if the opinions of the underprivileged members of society don’t reach the final decision-makers once they are shared. There’s a need for a respected channel that links levels of government and all stakeholders so that the identified obstacles or proposals made by people at the local level, especially those that fall outside the competence of local government, can get to those who can do something about them.

Dialogue in Partnership

For the proposed solutions to take practical shape, they must firmly be embedded in people’s daily lives, language, and customs. They must be presented and explored in terms that make direct and immediate sense. Otherwise, their relevance and impact will not be realised.

The designing and implementing of the solutions should include high levels of experiential involvement, as well as visual imagery, and, where possible, they should appear as having ‘emerged from the culture of silence and understanding’ of which necessitous are a part. The solutions should be rooted firmly in the realities of the struggles of the struggling members of the community.

In this partnership, the policymakers become more facilitators of a dialogue than instructors in a top-down structure of command or interaction. In this approach, both facilitators and the community are mutually learning from their varying experiences and knowledge as they create long-lasting solutions to the challenges faced in the community.

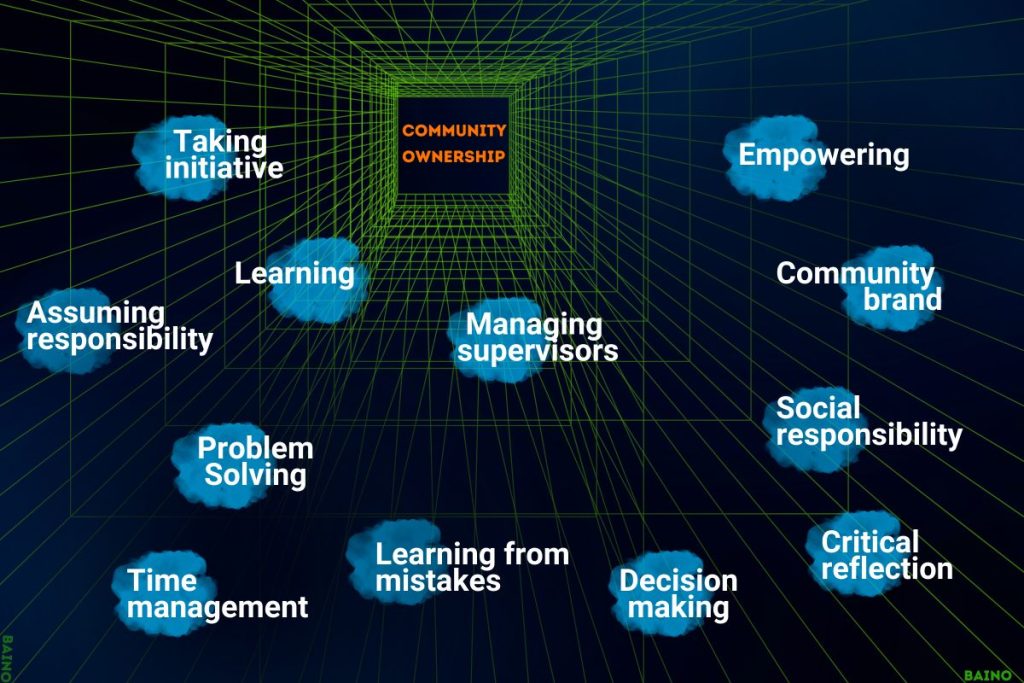

The underprivileged members of the community, the illiterate, and the marginalised are not ignorant, especially regarding the life they lead day-in-day-out. They are the experts in their lives, so they shouldn’t be treated as specimens or objects in their unfolding history and social life. They need to be given a chance to become the subjects of their futures. This change involves independence, empowerment, freedom and understanding, and ownership.

Rather than being passive recipients of information, they become the agents of the fundamental transformation of their reality. It is an approach that doesn’t emphasise charity and assistance. Instead, it encourages the active participation of the deprived in understanding and transforming their conditions. It builds a sense of their right to be responsible, dynamic, and critical change agents.

Such responsibility cannot be learned intellectually; it must be gained through experience.

This is how the unprivileged members of society get a chance to learn, build their knowledge and competence, and become responsible citizens. And in this process, new knowledge emerges through the invention of new solutions and re-invention and transformation of themselves as individuals.

Another means of involving people with low incomes in policy-making is to work with ‘experts-in-experience’. These people themselves used to be very poor and gradually learnt to deal with their experiences and eventually improved their lives. The experience they went through can be shared as an inspiration to those who find themselves in the same challenging conditions that the experts overcame.

Experts-in-experience can be a great resource in suggesting some of the methodologies that can be applied to bridge the gap between the unprivileged and policymakers. They can be contracted, trained and given professional roles that help in the fight against poverty.

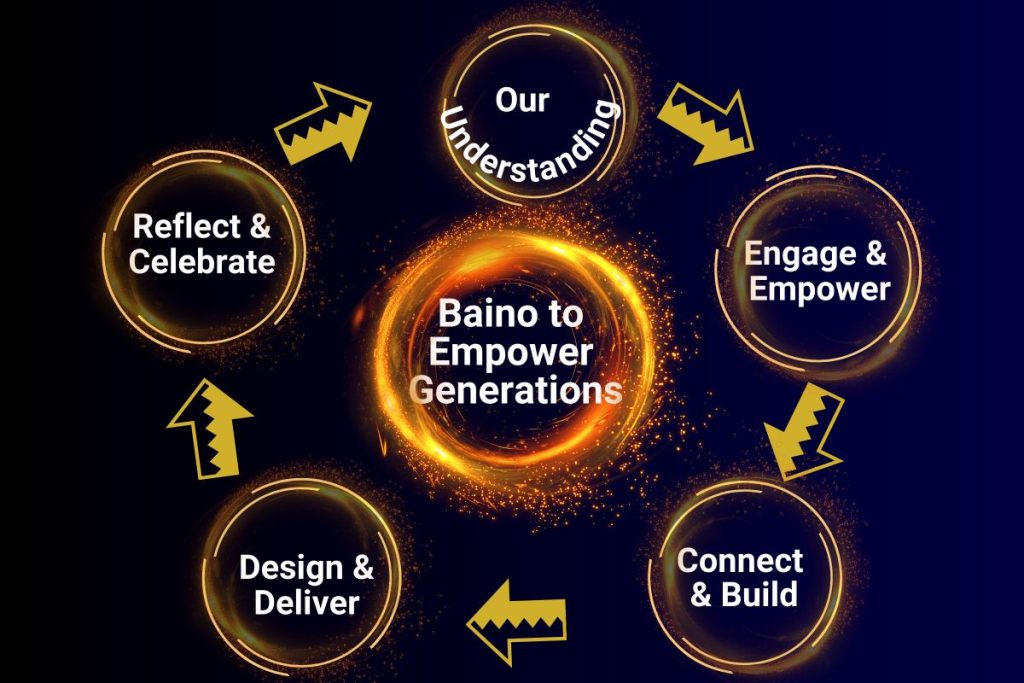

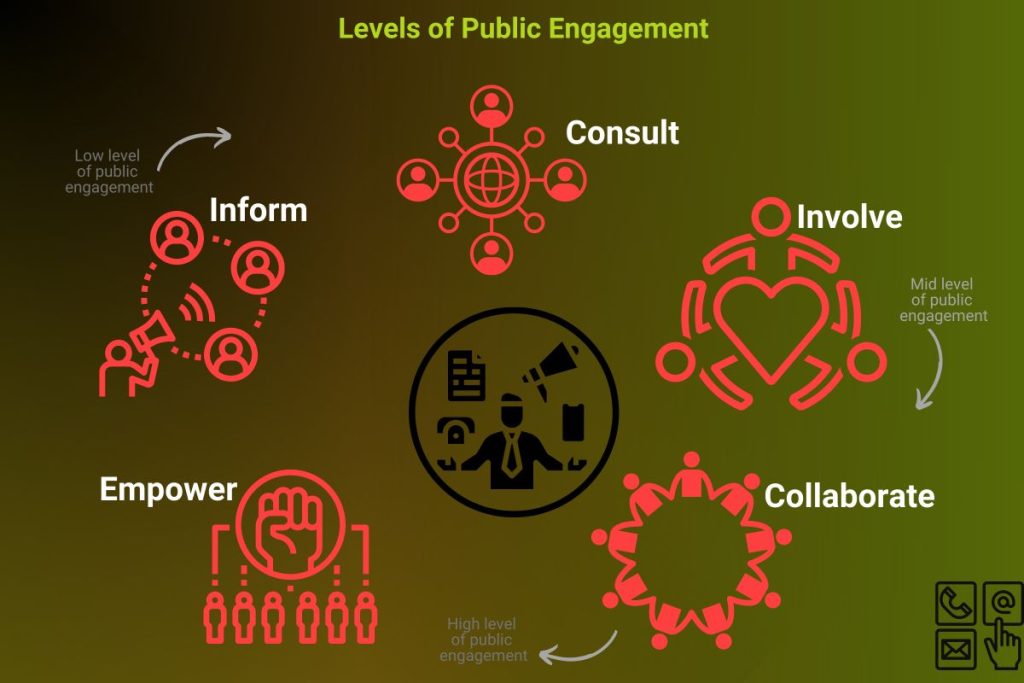

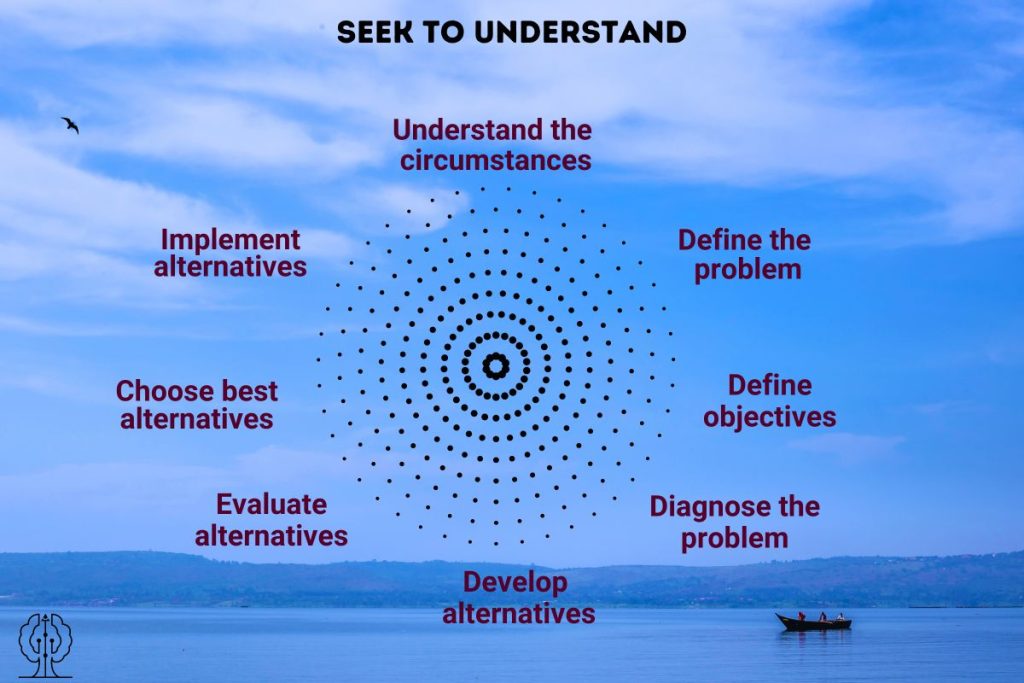

Methods of Engagement

Public engagement is an umbrella term encompassing numerous methods for bringing people together to address issues of public importance. These several methods are not static and not necessarily universal in practice. This is why defining public participation or engagement isn’t an easy task.

The term encompasses a wide array of activities and processes that sometimes can be confusing for civil servants, who are simply trying to understand their responsibilities, and citizens, who may have never attended a public meeting. This explains why it’s always essential to agree with this term as a framework and use it as a base to explore some variations in the context of the Busoga region and her specific challenges.

A framework for understanding the varieties of participation available to local leaders, organisers, facilitators and all other stakeholders, as well as some of the positive and negative features of each option, is more likely to create positive and scalable outcomes.

Designing a framework of operation will offset challenges determined by a lack of definitional clarity that might undermine the goals and benefits of participatory forms of engagement. The framework will remove misunderstandings and simplify the process, helping participants better understand engagement and how it should seek to solve the pressing challenges.

Engagement Models

There are direct and indirect forms of participation in democratic systems or public processes.

Indirect participation takes the form of electoral voting, financial contributions to political campaigns, political protests, corporate lobbying, and other activities that indirectly affect the outcomes of democratic processes by either (1) influencing the makeup of representative legislatures or (2) influencing the elected representatives who determine public policy.

Direct participation encompasses activities by which people’s concerns, needs, interests, and values are incorporated into decisions and actions on public matters and issues.

It is usually the duty of facilitators or local leaders to choose an appropriate engagement strategy or format for the task at hand. All methods of engagement have their strengths and limitations. They can also complement each other very well if handled right. This complementation is sometimes called a ‘multichannel’ system for engagement.

Intensive Engagement

Some engagement levels are more intensive, informed, and deliberative. Most of the actions may happen in group discussions. They may include youths, families, or community member groups. Usually, they are inspiring, motivating, collaborative, diverse in background and personally transformative for participants and communities.

Mild Engagement

This kind of engagement is less intense. It’s faster, easier, and more convenient. It includes various activities that allow people to express their opinions, make choices, or affiliate themselves with a particular group or cause. It is, however, less likely to build personal or community connections.

Examples of mild engagement include polls, surveys, petitions, and other activities that either (1) educate community members about an issue or (2) solicit their views on an issue, which extends to information booths, open houses, fairs, social-media groups, or other mechanisms by which community members and constituents can submit feedback by mail, phone, email, or online form.

Unlike intense engagement, which focuses on empowering groups, mild engagement allows individuals.

In mild engagement, individuals are provided with opportunities to express their ideas, opinions, and concerns in a way that requires only a few moments. Consequently, it is quicker and cheaper.

For this reason, engagement practitioners are often advised to blend the two types of engagement.

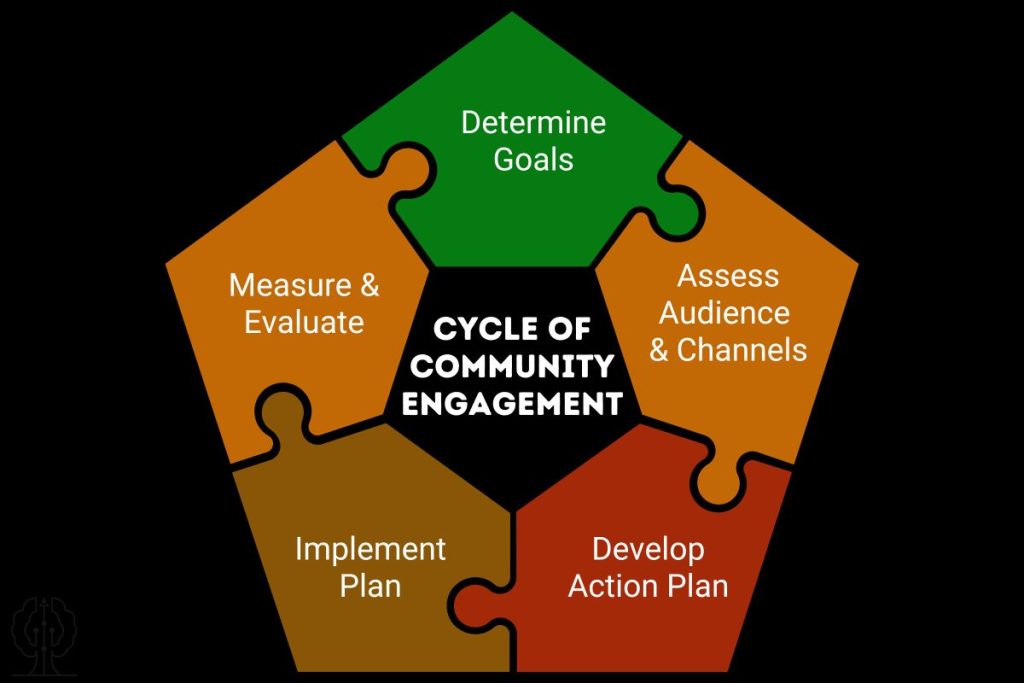

Engagement and Evaluation Process

Engaging all stakeholders in community manoeuvres is crucial in the evaluation and assessment process of policies. The evaluation of policy measures does not always happens systematically, and policy-makers only sometimes include public participation as a vital part of the process. However, the involvement of citizens—particularly the underprivileged—in the evaluation of policy measures is a necessary phase in the follow-up of policy implementation.

It is the local members who experience poverty that, based on their daily evaluation of the measures taken, can inform policy-makers of what works and what does not based on their own experience.

An evaluation may be applied in three ways: evaluation as a phase in the policy cycle (policy-making, implementation, evaluation), evaluation of the participation of citizens in the ‘evaluation’ of public policies, and ‘evaluation’ of existing channels for participation.

Accountability and evaluation are of extreme importance, especially in corrupt communities where there can be a tendency to provide ‘false support’ to maintain the reliance of those in need on those who benefit from the poor or the marginalised.

For the process to be successful, it should start with a change of mentality among local authorities and those above them. They must be willing to change and adapt to practices that view and treat all community members as a part of the actual implementation process of supportive projects and community programs.

It may take time and room for adjustment from both parties, but it’s a necessity and well worth the effort. All leaders are called upon to embrace these efforts and seek to bring them to fruition. As a reminder, outstanding leadership is perhaps the most crucial feature of a great society.

We ask all region members, near and far, to join in solidarity and open their hearts and minds to all forms of experiences presented to build a society determined to accomplish Busoga’s vision. First, however, we must wage war against poverty, fight a noble fight, and win.