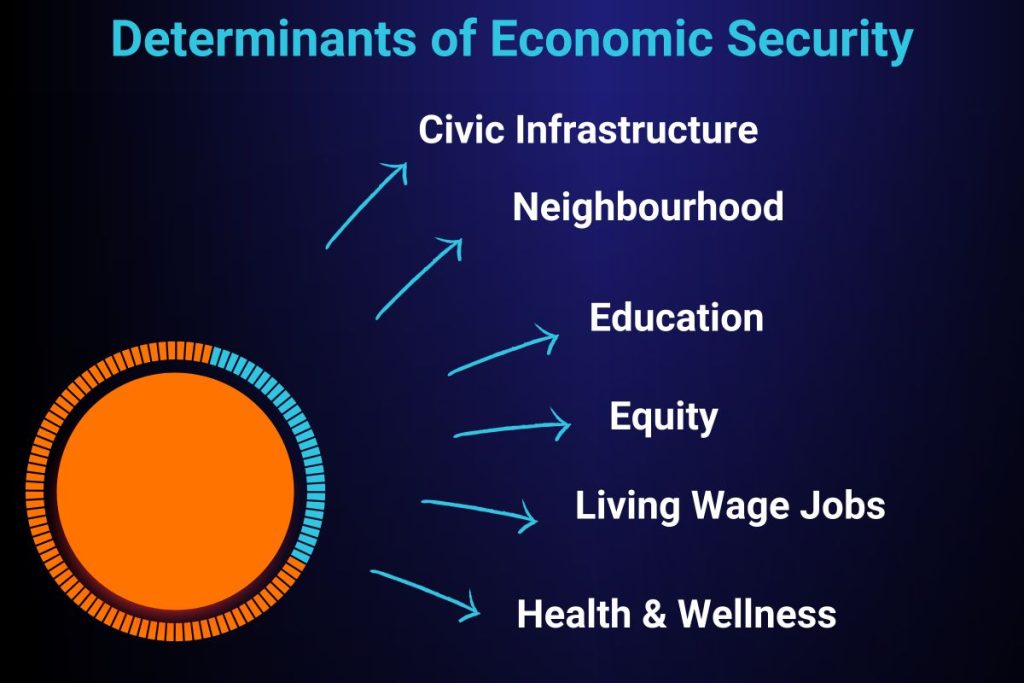

Economic security strengthens tolerance and happiness, as well as growth and development.

Broadly construed, economic security is the ability of people to meet their needs consistently. It is connected to the concept of economic well-being and the notion of a modern welfare state. It is a governmental entity that commits itself to baseline guarantees for its citizens’ security.

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), an organisation that tries to improve economic security globally, defines economic security as the ability of individuals, households or communities to cover their essential needs sustainably and with dignity. This can vary according to an individual’s physical needs, the environment, and prevailing cultural standards. Food, basic shelter, clothing and hygiene are essential, as do the related expenditures: the vital assets needed to earn a living and the costs associated with health care and education.

Economic Security services seek to establish if people affected by any form of crisis and conflict or major challenge can sustainably cover their essential needs. If they cannot, they help protect lives and restore livelihoods.

ICRC identified five key livelihood outcomes to track economic security: food consumption, food production, living conditions, income, and the capacity of civil society organisations and the government to meet people’s needs. All related efforts are driven by striving to be as accountable as possible, providing relief support to make life bearable in challenging times.

Economic security staff are, therefore, experts in livelihood analysis, nutrition, agronomy and agricultural economics, veterinary science, livestock production and management, and financial administrators.

Cultural standards play a role in determining what’s included in the list of essentials for economic security, meaning that economic security and how it is managed must be flexible and has indeed changed over the years.

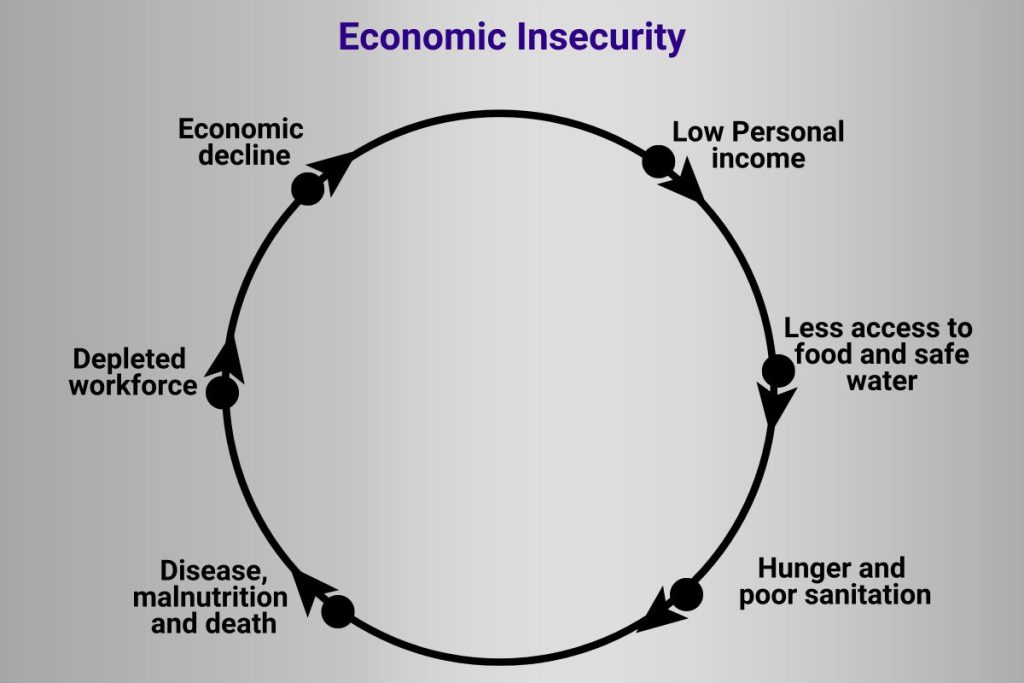

Attempts to ensure economic security are meant to check against instability in the marketplace, which is increasingly common in this modern world. ‘Economic insecurity’ happens when there aren’t enough resources to pay for food, housing, medical care, and other essentials.

The success of a society depends on whether all people, regardless of their social affiliation and positions in society, have the opportunity to thrive. They must have the skills and resilience to withstand hard economic times and grow their incomes.

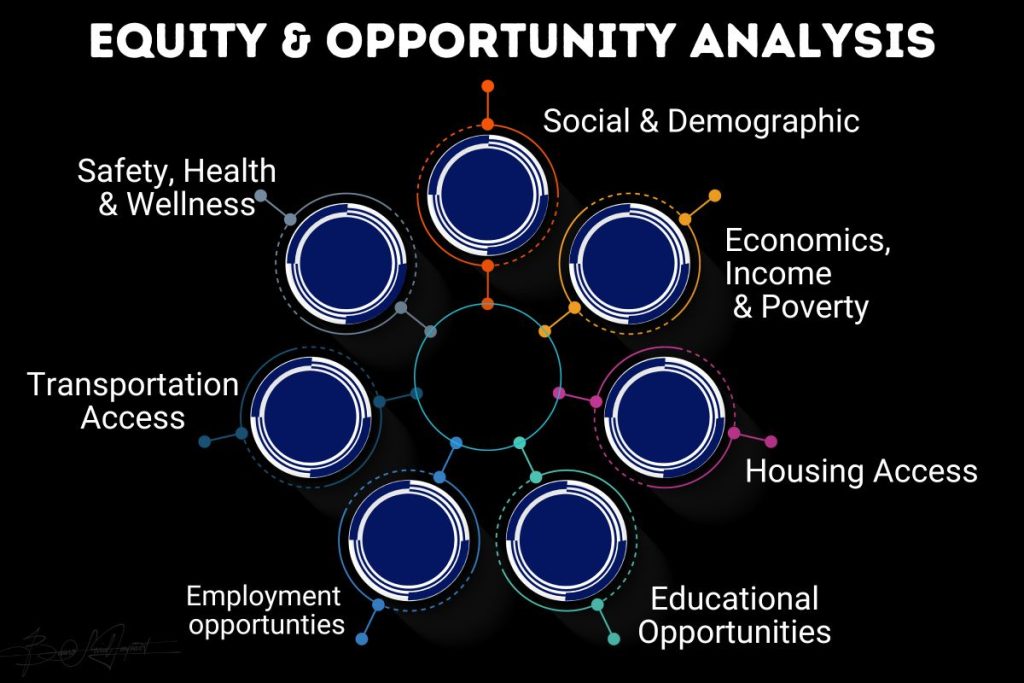

Economic security programs such as social security, food assistance, tax credits, and family assistance can provide opportunities by amending short-term poverty and hardship and, by doing so, improving people’s long-term outcomes. They also challenge barriers to opportunities, including discrimination and disparities in access to employment, education, and health care.

In nations where such services and related programs are provided, they have reduced poverty for millions of people—including children—who are highly susceptible to poverty’s ill effects.

Economic Insecurity

Poverty and economic insecurity are not synonymous. However, those who are economically badly off or unemployed, face discrimination or segregation or lack access to meaningful resources have to struggle daily, worrying about what lies ahead and being unable to exercise or develop their capabilities.

While notions of poverty overlap with insecurity, one could exist without the other. The same is true of the overlap between inequality and insecurity. Inequality is part of insecurity, especially when that inequality is substantial. And the unequal distribution of insecurities is part of socio-economic inequality.

Some people and communities are dreadfully insecure but may not be poor by conventional definitions. Others may feel relatively secure in themselves, even if they are inadequate in an income or property sense. But it stands to reason that income poverty and inequality are significant predictors of the incidence of insecurity—which is undoubtedly an intrinsic aspect of poverty. Many members in the Busoga region are insecure, in all senses—the kind worse than poverty—as they continue to face conditions that can only lead them down that path.

The dream of this service is to ensure that more people find opportunities to work in dignity for the benefit of their families, their communities and themselves.

All human beings need a sense of security to get a sense of belonging, a sense of stability, and direction in life.

When people are denied the opportunity and access to resources – and eventually lack basic security around themselves, in their families, workplaces and community, they become frustrated and can exhibit socially irresponsible behaviours. Moreover, periods and areas of mass insecurity have historically always bred intolerance, extremism, and violence. This is what we see around the world today.

Insecurity is instrumentally depriving. It induces people to be less innovative than they otherwise would be and less likely to take productive risk-taking options. Especially communities facing systematic insecurity are increasingly exposed to all sorts of risks and uncertainties.

Insecurity shortens people’s time horizons, makes them more opportunistic, and narrows their choices. It heightens uncertainty and stresses vulnerability. Generally, its cost extends beyond visible, including psychological, financial and other social costs.

Unfortunately, in recent decades, and stretching into the future, ordinary workers and working communities—and societies on the edge of the capitalist economy—are obliged to bear most of the worst forms of insecurity. In contrast, large-scale asset-holders seeking wealth, status and power are relatively well shielded from insecurity.

Understanding Economic Insecurity

Giving a precise, practical meaning to economic insecurity can be challenging. People’s feelings of insecurity often draw on their experience—experiences of economic shock create insecurity—but they also have a prospective risk-related dimension.

Despite its importance for well-being, economic productivity and social and political stability, economic insecurity often goes unmeasured. Reliable and widely disseminated data comparable across countries and essential to inform policy must be inclded or improved. Therefore, efforts must be undertaken to improve this fundamental right’s measuring and evidence base.

Actual risks can cause insecurity or be based on people’s perceptions. Despite its many facets, two elements are common to most definitions of economic insecurity (1) people’s exposure to—or expectation of—adverse events, and (2) their (in)ability to cope and recover from the consequences of such events.

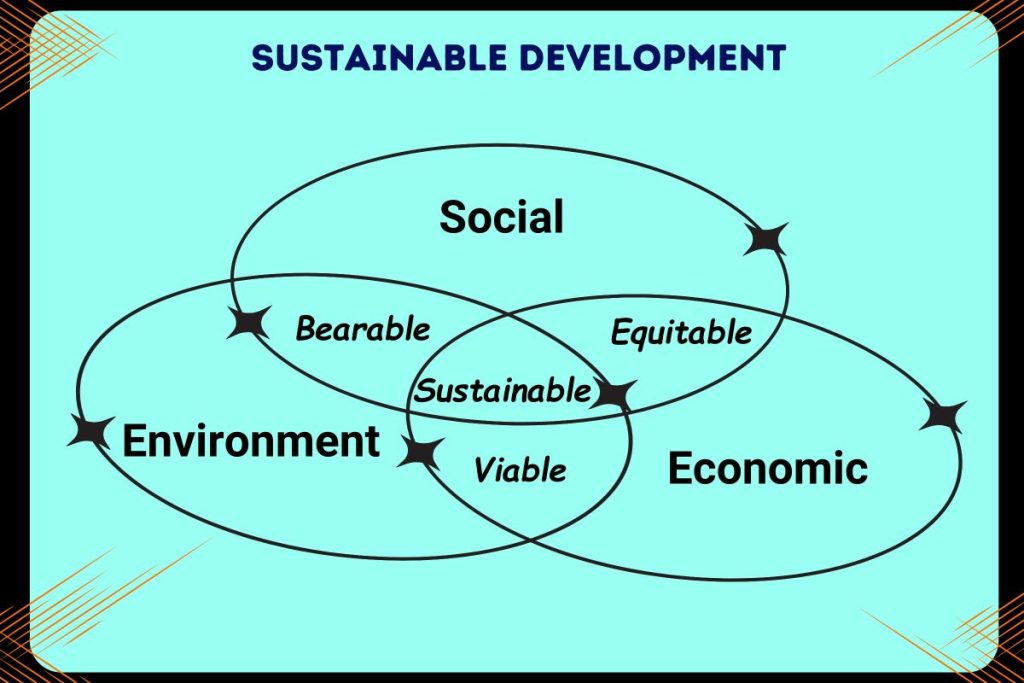

This brief contends that the risk of adverse events is growing while people’s abilities to cope and recover are not improving correspondingly. This supports the case for bringing economic security to the forefront of a new global deal, leveraging the available opportunity.

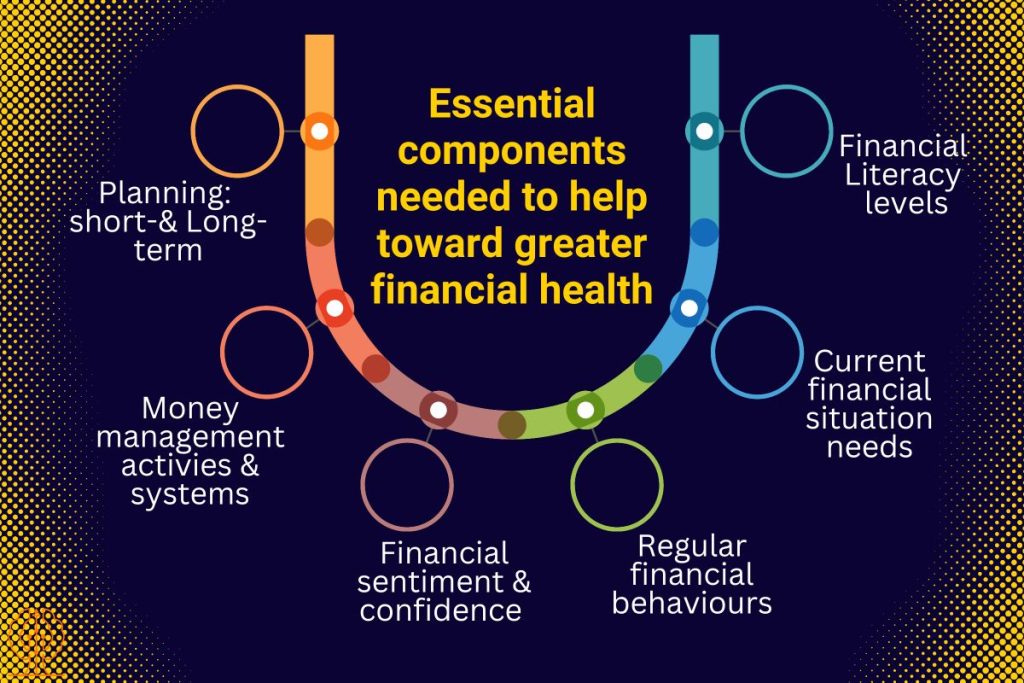

Economic security is a cornerstone of well-being. Economic stability and some degree of predictability enable people to plan and invest in their future; they encourage innovation, reinforce social connections and build trust in others and in institutions that provide the required services.

Worry and anxiety about the future have adverse health outcomes, ranging from mental health problems to heart disease and increased unhealthy living.

The question we need to ask ourselves is, how do we enable access to opportunities for everyone to engage in meaningful work and acquire assets that help their families support themselves and advance in life?

Indeed, economic security relies on the perception of actual general safety and quantifiable material or financial conditions.

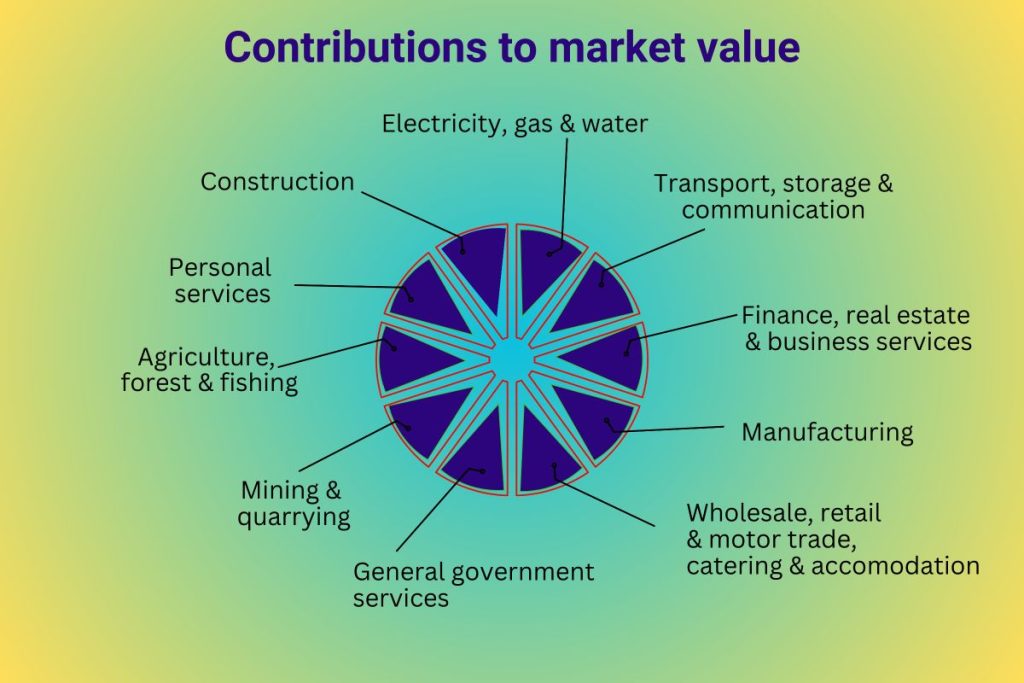

Nationally speaking, economic security refers to a country’s ability to pursue its own developmental goals for its economy, and it is often explicitly linked to national security. This encompasses broad concerns about the balance of trade, the impacts of foreign investments on national markets, and private-public partnerships. Traditionally, economic security was ensured by assets, labour, family and charity.

While conventionally calculated in gross domestic product (GDP) terms, national economic well-being—a concept intimately connected to economic security—has increasingly broadened to include factors such as national happiness.

Economic Security Matters

Economic security matters because that’s all there is, especially in this modern world.

Basic security matters. Without it, there are fewer incentives to study, learn, and grow, and confidence suffers. Without it, people cannot plan for their future or their children’s future. In addition, people lose the sense of control over their lives and soon end up becoming dependent on the generosity of others and on luck. That’s not the way to live.

Economic security matters because human freedom and dignity matter to every human being. Equally, it should matter to every position of leadership and service, particularly in light of these persistent economic and social development challenges. It should become a high-priority policy matter.

Security matters because freedom and self-determination matter. Absolute freedom cannot exist unless a certain level of basic economic security exists.

From its inception, the United Nations recognised the significance of economic security for well-being. Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that everyone has the right to an adequate standard of living ‘and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond one’s control.’ Advances towards universal health care coverage, access to quality education and the promotion of decent work can promote greater economic security.

The desire for economic security is a powerful, universal sentiment that most people can relate to. It is linked to poverty or other related hindrances and a growing gap between people’s expectations and their actual situation. Because it affects so many people, a growing sense of economic insecurity can have considerable political impacts.

A new global ideal must be based on recognising economic security as a human right, a universal concern and, therefore, a global responsibility. A global deal promoting economic security should enjoy broad approval as it can help build coalitions. In doing so, it can encourage greater international coordination in matters of labour rights, social protection floors, the portability of social protection benefits, public health and the type of taxation needed to provide universal access to quality public services.

Risks are Growing

Fears related to economic insecurity are on the rise. Changes in the world of work, together with globalisation and technological breakthroughs, have benefited many people but are also putting many others at a disadvantage or risk. These long-standing trends, which have raised aspirations but also fears, are compounded by evolving threats, including those brought about by climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic.

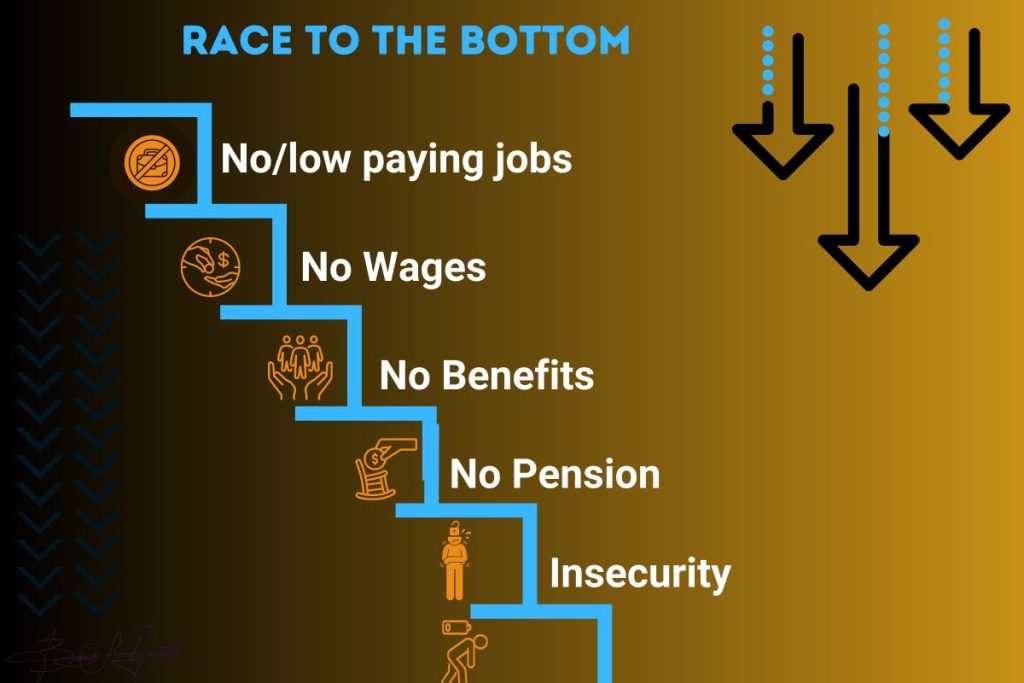

Especially in developing countries, high levels of informal employment continue to affect income stability. Growing job insecurity, increasingly insecure and low-paying jobs, and prolonged unemployment are the primary reasons for rising economic insecurity in developed countries.

With growing job insecurity in many countries and insecure working conditions in most, countless people can no longer rely on stable, decent work to provide economic stability throughout their lives.

Even on a worldwide scale, there is so much that is exacerbating the sense of insecurity. Among other rapid transformations, issues like the effects of climate change are threatening lives and livelihoods on a large scale. Increased awareness of climate change and its many implications has increased uncertainty about the future. It has raised people’s concerns about their well-being in the long run. Even though its effects are shaping anxieties worldwide, its impacts will be uneven. In all these uncertainties, people in the poorest countries stand to lose the most.

But the link between the COVID-19 crisis and insecurity goes both ways. While the impact of the crisis on insecurity is clear, the economic insecurity that preceded the crisis has amplified its effects. Many people in low- and middle-income groups lack financial resources to weather shocks. This is particularly the case where job insecurity, including in the informal economy, hinders access to healthcare and social protection, including unemployment insurance.

In many countries, the impact of the COVID-19 crisis is more severe on women, for instance, because of their over-representation in informal employment. The crisis has spotlighted massive inequalities in exposure to the virus, the ability to work from home, access to adequate health care and e-learning, and social protection. It has exposed the precarity of many people’s lives and revealed the enormous risk and uncertainty in today’s society.

This crisis comes amid a rapid technological change driving profound changes to many aspects of life—from employment to civic participation and governance—and generates uncertainty about the future. Workers fear that robots and artificial intelligence will replace their jobs. New technologies already carry out many tasks that humans could only perform until recently.

As much as technology has shown to be beneficial, particularly in terms of increased connectedness and easier access to the expanding amounts of information, it also poses substantial challenges in our lives. For instance, it dangerously deteriorates people’s sense of security and trust in each other.

Public discourse is changing as news—both genuine and fake — spreads at an unprecedented pace. Social media has enabled the targeting of information campaigns, manipulated views and influenced elections, challenging, effective governance and, sometimes, eroding trust in institutions.

Need of New Updated Policies

People in poverty are more exposed to risks from adverse events, from ill health to the growing impacts of systemic shocks such as a deep sense of neglect, climate change and health and security concerns, and pandemics, among others. Even those who now live way above the poverty line feel economically insecure.

Many societal changes are increasing the exposure of low-income groups to adverse events, and their ability to cope and recover seems to decline.

Several changes in the structure of families and households have shuffled roles in traditional sources of informal support. At the same time, public institutions, policies and governance systems are struggling to adapt to rapidly changing needs, that is, if they even understand the changes occurring in people’s lives.

New forms of employment and work are emerging, partly because of digitalisation and automation trends. There is little employment security, and yet access to social protection is limited.

Globally, economic integration has promoted competition among countries, including on working conditions, and has constrained national policy space. Social protection systems, which are meant to address economic insecurity, cover less than half of the world’s population.

In many countries, the increasing cost of health care, education and housing has also become an essential source of economic insecurity, possibly impacting future generations.

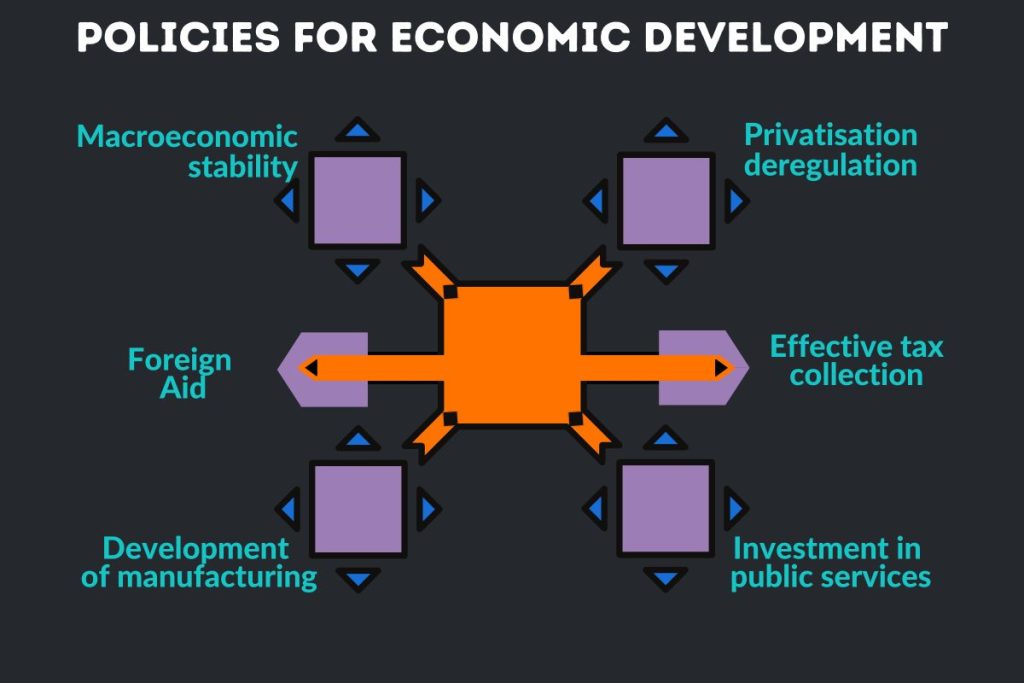

Privatisation has increased the cost of essential services. It has even priced out people into poverty—or otherwise affected the quality of services the most disadvantaged receive. All these changes are happening when further attention to the basic needs of people, especially the most vulnerable, is increasingly becoming important. Therefore, it is critical to redraw and update policies that were formerly dependable in this modern era.

The measurement and analysis of economic insecurity matter extensively in developing countries where social protection systems and other risk-pooling mechanisms are weak. At the same time, levels of informal unemployment are higher.

Unemployment, health shocks, and old age are leading events likely to trigger downward shocks to income. The role of health shocks and medical spending are potent drivers of economic loss and impoverishment. It’s estimated that one-third of households who fell into poverty over time did so due to poor health and high healthcare expenditure episodes. Often, however, a series of shocks to income—and the debt obtained to smooth income in the face of insufficient assets—paves the path to poverty.

Ensuring Economic Security in Busoga

Most governments try to preserve economic security through social safety nets that guarantee minimal citizen protections. However, because there are often disparities in how economic instability is experienced and the current economic condition in Busoga region, any proposed solutions have to dig deeper than that.

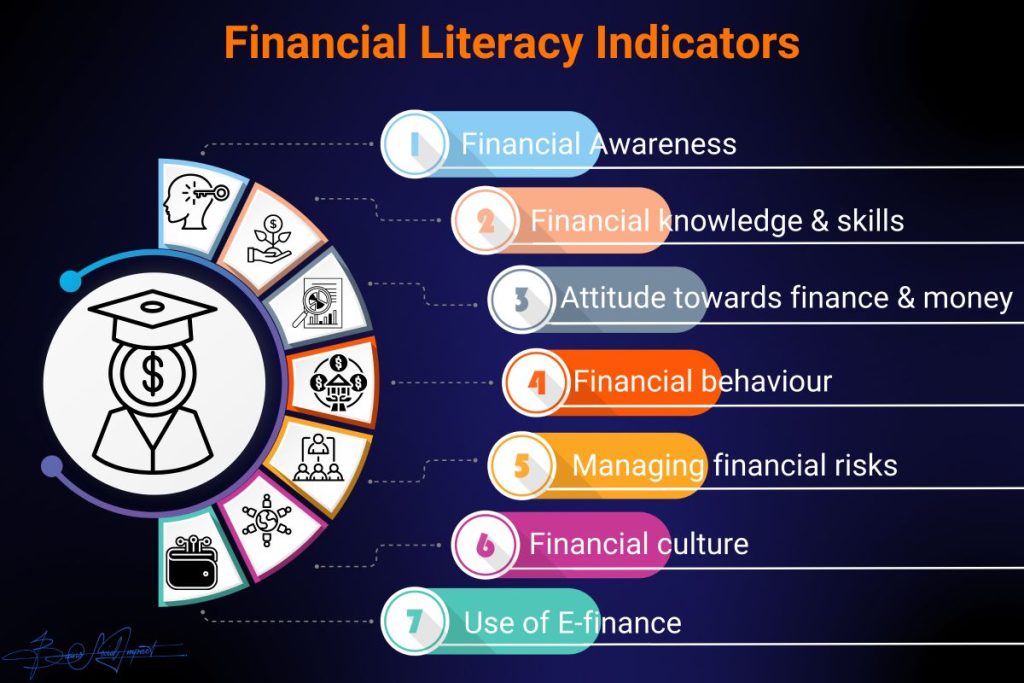

Given the two scourges of high illiteracy and abstract poverty in the area, the solutions that seek to minimise these disadvantages have to invest in robust training to, first and foremost, change the course of people’s behaviours. Coaching, education and training must first be provided to align the people with the intended objective, or else most of that effort won’t create noteworthy results.

Unlike financial literacy, financial capability programs—when done right—can help people to change their financial behaviours, work toward specific financial goals and truly improve their financial well-being on a long-term scale. Coaching designed to support a field of practice is necessary for working low-income families to move from surviving to thriving as an integral component of their success.

There is a need to build a training or education progression for working families that can help set a framework which will operate as a guideline in delivering critical services, and any related support, to those who need it most: low-income families. As mentioned, all services and associated efforts must follow an intentional and thoughtfully integrated approach designed to make it easier to attain the region’s objectives.

Through classroom training, in-field training, coaching groups and learning labs, participants can receive hours of training and education in a given period. And ongoing learning and continuing education can ensure that participants remain on their chosen course.

To realise such a change, community members need a deep understanding of their current issues and, most importantly, how and what caused them. This is the only way they will be able to uncover the masked long-term inequalities they face and devise a lasting solution for them.

The ongoing support can include encouraging low-income families to build savings for their children’s future education and further investments. Programs designed to provide safe, easy-to-access, trusted, and low-cost opportunities to make savings can be a part of the training process. The major challenge is changing people’s behaviours to align with the objective and having the skills and support to make each family’s dreams a reality.

Research shows that organisations whose services are integrated around three core elements: employment, income support and financial coaching, make the most difference in individuals’ financial stability and mobility. Consistent one-on-one coaching can be an integral component of service delivery. It can become a reference in helping clients set goals, develop plans and change behaviours. Supporting agents are almost inevitably developing dependable, long-term client relationships versus the traditional one-time transactional client experience. This approach will help clients overcome current deep-rooted barriers to advance economically in a reliable way that can be built upon for other advancements.

Investment in training programs and coaching services will drive families and individuals to achieve and sustain economic security in a much stronger, collaborative system.