Discover how the education crisis in Uganda is deepening poverty in the country’s poorest communities.Learn how your support can improve literacy, empower children, and create lasting change.

Where literacy begins, everything changes — from a child’s future to an entire community’s destiny.

Literacy is one of the clearest indicators of a community’s health and potential. It shapes the quality of life, unlocks opportunity, and drives both economic and social transformation.

According to the Uganda National Household Survey, literacy means the ability to read with understanding and write a simple, meaningful sentence in any language. But real literacy goes further — it’s the ability to interpret, question, and fully engage with the world. These skills are not just academic; they are essential for dignity, progress, and survival in today’s world.

The Education System in Uganda

Uganda’s system comprises:

- 7 years of primary school

- 4 years of lower secondary (O-Level)

- 2 years of upper secondary (A-Level)

- 3-5 years of tertiary education

Since 1997, Universal Primary Education (UPE) has offered free primary schooling. Universal Secondary Education (USE) followed in 2007. Yet, while tuition may be covered, families still bear the costs of uniforms, supplies, boarding, and healthcare — costs too high for many in poverty-stricken rural areas like Busoga.

Both public and private institutions provide tertiary education, and informal learning programs offer vocational and hands-on skills to those left out of formal schooling.

Education is an Empowering Machine for Lasting Change

The Harsh Truth: Low Standards, High Hurdles

The truth is stark. Despite UPE and USE’s promise to bridge the literacy gap, the quality of education remains painfully low — especially in rural communities like Busoga.

Many schools suffer from inadequate resources, poorly trained teachers, and failing infrastructure. Accountability gaps, language barriers, poor program design, and uneven distribution of resources deepen inequality.

The troubling result:

- Many children leave school without mastering basic reading or math.

- Some primary school students struggle to write their own names.

- Busoga consistently ranks among Uganda’s worst-performing regions in national exams, as reported by the Uganda National Examination Board (UNEB).

Families in Busoga are left to wonder: Does sending our children to school even make a difference anymore?

Morale is low. Children’s relationship with learning is strained. And the vision of education as a path to prosperity feels increasingly out of reach.

This is why African charities for school projects — like Baino Social Impact — are stepping up to sponsor students in Uganda, build better classrooms, and help restore public confidence in education.

We’re not just fighting illiteracy — we’re fighting for the right of every child to dream beyond survival.

Why This Matters — And How You Can Help

Education is the surest path to economic opportunity, health, and gender equality. To help end poverty in Uganda, we must strengthen rural education from the ground up.

Your support can help us:

- Sponsor students so they can stay in school and succeed.

- Build and equip classrooms that foster real learning.

- Train teachers to deliver quality, inclusive education.

- Advocate for policy changes that make lasting impact.

Together, we can help end poverty in Uganda, promote literacy in Africa, and empower communities to chart a new course for generations to come.

Join the mission. Change lives in Uganda’s most impoverished communities.

Many Children in Busoga Are Still Left Behind

Education in the Busoga Region is Alarming:

Despite the promise of free primary education, far too many children in Uganda’s Busoga region are out of school — and at risk of losing their future.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights declares that every child has the right to free primary education. Yet in Busoga, poverty, gender inequality, and systemic neglect keep thousands of children out of school.

Many children do not attend school

Many children do not attend school—not because they lack dreams or the will to learn, but because the world around them has failed to build the road to the classroom. Life keeps pulling them away from the blackboard. Some walk for miles, only to turn back. Others stay home to fetch water, care for siblings, or simply because no school exists nearby.

Their childhood slips by—brilliant minds dimmed by silence, dreams delayed by circumstances they did not choose. When poverty speaks louder than potential, and survival eclipses study, we lose not just students—we lose future teachers, healers, and leaders.

A recent Uganda National Housing Survey (UNHS) revealed:

- The proportion of girls with no formal education is nearly three times higher than that of boys.

- While 24% of those in town complete primary school, only 14% finish secondary school, and 20% go beyond.

- About 40% of rural residents lack formal education, compared to far fewer in urban areas.

Why Are So Many Children Missing School?

The reasons are complex — from financial hardship to cultural barriers, from fragile infrastructure to sheer distance.

- 19% of children don’t attend school because their parents didn’t want them to.

- 14% found schooling too expensive despite “free” education.

- 6% had to help with farming or household work to support the family.

- Teenage pregnancy forced over 4% of girls aged 6–24 to drop out — a figure that surged during the Covid-19 pandemic.

- Other barriers include sickness, orphanhood, disability, poor academic performance, long distances to school, and low interest (often driven by discouraging conditions).

👉 Income-related reasons alone account for over 65% of dropouts.

Other significant reasons for not attending school were:

- Student's lack of interest or unwillingness to attend

- Sickness and calamity in the family, like the death of a breadwinner or being orphaned

- Poor academic progress

- School too far away

- Being disabled

- The costs associated with education for both boys (34%) and girls (35%), and Lack of funding (boys 33% and girls 31%).

- More than 4% of girls aged 6 to 24 left school because of pregnancy.

- Teenage pregnancy has increased tremendously, especially during the Covid-19 period.

The Cost of Distance and Poor Infrastructure

- 47% of communities say the nearest government secondary school is at least 5 km away.

- Only 4% of communities have a government secondary school within their Local Council (LC1).

- 41% report that even primary schools are outside their immediate community.

- Vocational and technical schools? Just 3% of communities have one locally — forcing families to send children to distant urban areas at unaffordable costs.

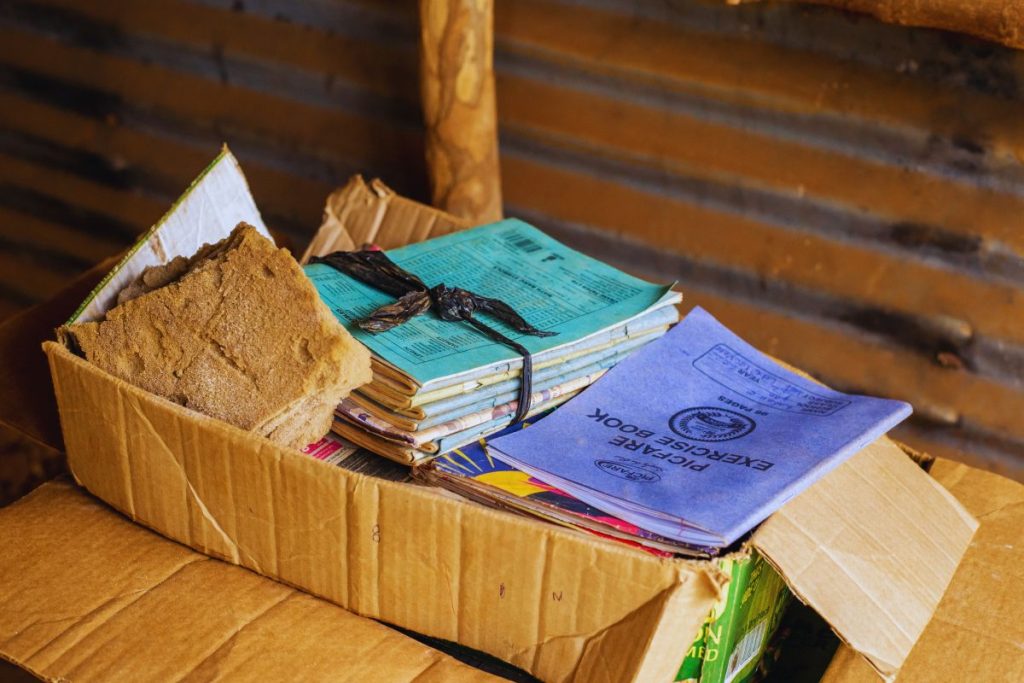

Private schools, often better resourced, are beyond the financial reach of most families. Even where schools exist, essential materials are scarce:

- Up to 10 children may share a single outdated textbook.

- Classrooms are overcrowded — exceeding the national average of 65 pupils per classroom, with Busoga ranking among the worst for adequate sitting and writing space.

Teacher Absenteeism and Hard-to-Reach Challenges

Teacher absenteeism is widespread in Busoga — the highest in Uganda. Many teachers juggle second jobs to survive, and others are deterred by poor roads and the harsh conditions of remote villages classified as “hard-to-reach” or “hard-to-stay” areas.

And so, the result is the low morale, poor learning outcomes, and growing disillusionment with public education.

The Human Right Failing to Deliver

Education is not a luxury. It is a fundamental human right, a basic need, and the gateway to a life of dignity and opportunity.

Yet children in Busoga are denied this right every day — not because solutions don’t exist, but because action has been too slow and support too thin.

Your help can make the difference:

- Sponsor a child so they can attend school and stay in school.

- Support building safe, well-equipped classrooms.

- Help train and retain qualified, motivated teachers in the region.

- Invest in vocational programs that give youth practical, life-changing skills.

This is how we fight illiteracy in Africa — one empowered student at a time.

Your compassion can help us break the cycle of poverty and illiteracy in Uganda’s poorest region.