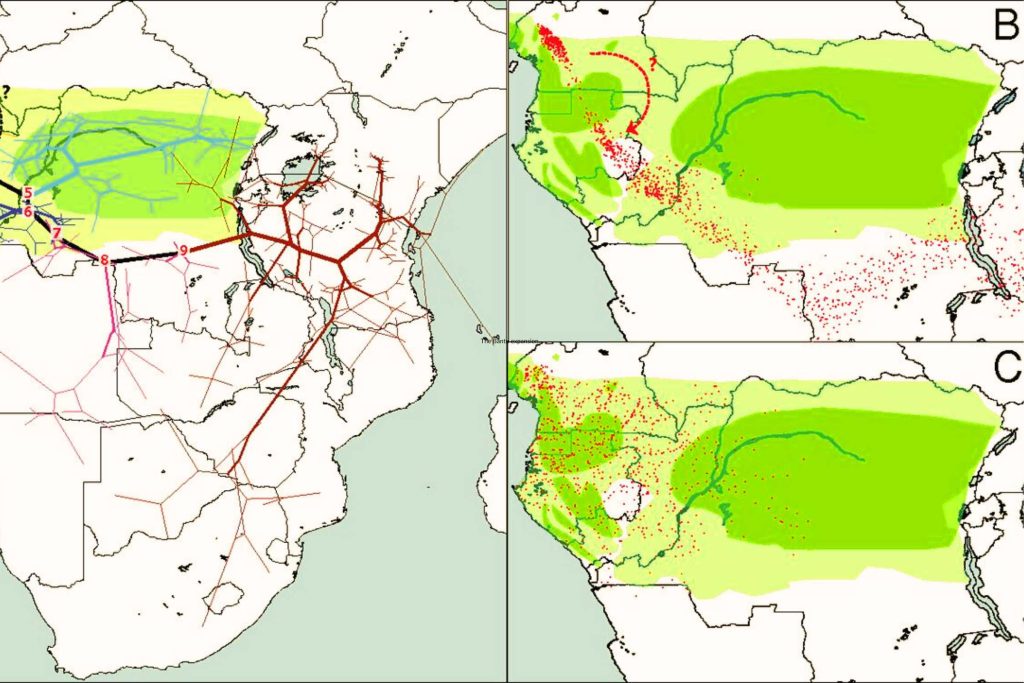

Historical research relates the origin and settlement of the Basoga to that of the Bantu speakers who entered present-day Uganda from the northern Katanga region of Central Africa between 400 and 1000 c.e.

Just like any other Bantu ethnic group in this interlacustrine region, the origins of Busoga are unclear to historians. In addition, due to the continuous movements and intermingling of the people within and around the Busoga region, its history is generally complex.

Busoga’s origins, however, have been associated with several legendary theories and traditions.

Beginning between 1250 and 1750, the Basoga migration and settlement in this present location was associated with two cultural heroes: Kintu and Mukama.

Kintu

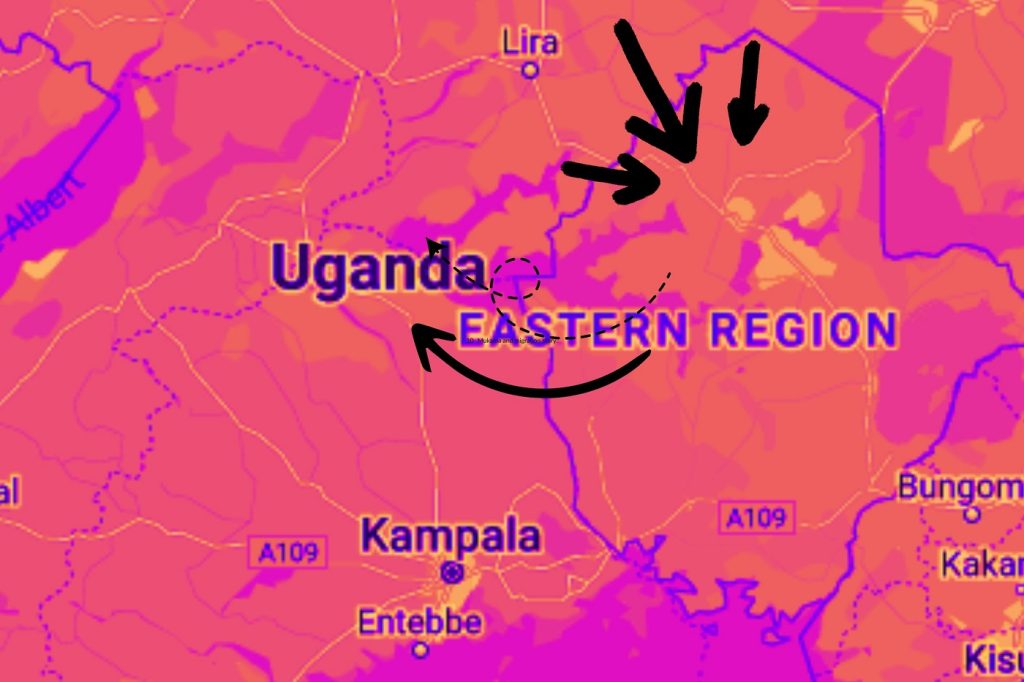

Generally, migrations around the Lake Victoria area are associated with Kintu, who is believed to have originated from the Mount Elgon area in the east and travelled to and through Busoga, establishing several states.

While on his journey, Kintu left his sons in Busoga as he continued farther west. When he later returned to Busoga, he settled at a place called Buswikira, at Igombe, Bunya. When he died, he was buried in this same place. It’s believed that, over the years, his tomb solidified into a rock. Later it became a designated centre of worship.

Mukama

In the period between 1550 and 1700, Busoga was heavily influenced and affected by the arrival of the Luo-ethnic group immigrants.

This new group settled across the northern and eastern parts of present-day Uganda. It is this group that is heavily associated with the famous figure, “Mukama”. He was the most influential leader of the Luo immigrants and is also traditionally regarded as the provider of all things.

Originating from the east, Mukama travelled westward. He stopped in Busoga and fathered children who themselves founded important states in the northern parts of Busoga. Later, he continued with his journey towards the states of the Bunyoro Kingdom in the northwest.

These Luo migrations turned Busoga into differentiated cultural zones consisting of the largely Bantu-influenced region around Lake Victoria in the south and the Luo-influenced area in the north, around Lake Kyoga and the Mpologoma River.

Byaruhanga Ndahura

Another oral tradition states that as early as 1233, Prince Byaruhanga Ndahura, who belonged to the Igaga Clan of the Bunyoro-Kitara Kingdom, arrived in an undefined territory, which he later named Busoga. He arrived in the company of his brother-in-law, called “Kisiki”, and with soldiers who belonged primarily to the Ngobi Clan of the Bunyoro-Kitara Kingdom.

Byaruhanga established six counties: Bugabula, which he entrusted to one of his soldiers, Gabula as Chief; Luuka, which he entrusted to Tabingwa; Busiki to Kisiki; Bugweri to Menhya; Bukhooli to Wakhooli; and Kigulu, which he preserved for himself because it was soon to be the seat of a kingdom he wanted to establish in due course.

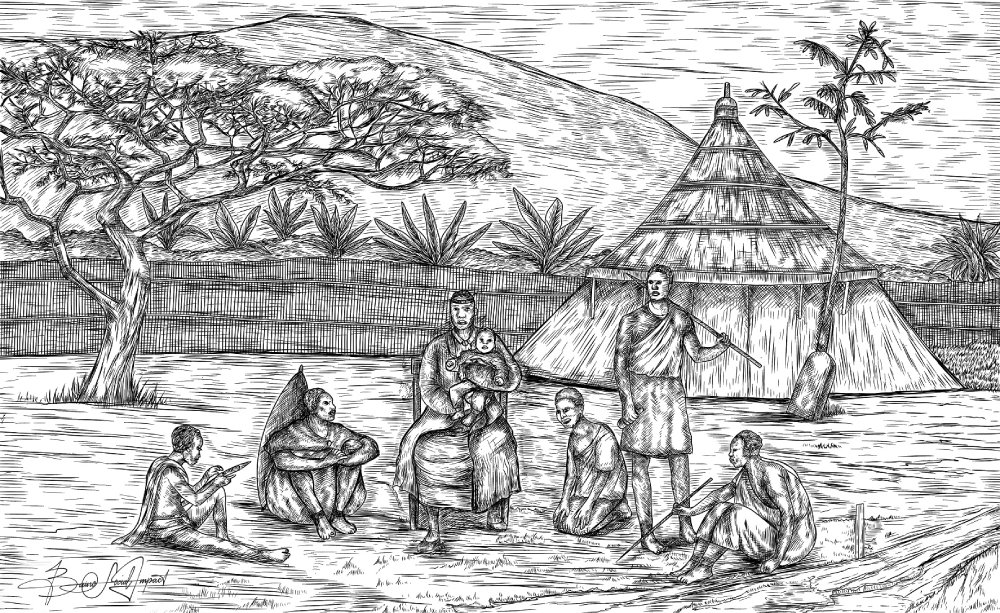

When Byaruhanga reached Busambira village, he was fascinated by the relaxed ambience of Nnenda Hill. He climbed to the top of the hill. On his way back, the natives, known for their hospitality, offered him a beautiful girl. When he received the news that she was pregnant, he was motivated to stay at the foot of Nnenda Hill for another two years until the child was born.

When the child was born, a baby boy, he named him Ndahura.

When Ndahura reached two years of age, Byaruhanga summoned the chiefs of the five counties and declared to them the formation of a new kingdom, with his son, Ndahura, as the first king. He decreed that the king would bear the title Isebantu (i.e., the Father of the People) and the five respective chiefs would be regents to the new king until he was old enough to rule by himself.

Byaruhanga declared that the kingdom, and the king, would be royal and hereditary, and so would be the chiefdoms and chiefs. Sons of those leaders, therefore, would be chiefs of their designated chiefdoms. They continued to preside over their respective dominations, employing the governing methods and cultural rituals of their father’s origin, the Bunyoro-Kitara Kingdom.

Prince Mukama Namutukula

Another oral tradition that hosts two mentions of the above theories states:

Prince Mukama Namutukula from the royal family (Babiito) of the Bunyoro Kingdom left Bunyoro around the 16th century and, as part of Bunyoro’s expansionary policy, trekked eastwards across Lake Kyoga with his wife Nawudo, a handful of servants, arms, and a dog. He landed at Iyingo, located at the northern point of Busoga in the present-day Kamuli District.

Prince Mukama loved hunting, and his adventures exposed him to the beauties of the newly found land. He sometimes engaged in blacksmithing, making hoes, iron utensils, and spears. Prince Mukama and his wife Nawudo bore several children of whom only five boys survived. On his departure back to Bunyoro, Prince Mukama allocated his sons areas in Busoga to oversee. The first-born, Wakoli, was given to oversee the area that became Bukooli; Zibondo was to administer Bulamogi, Ngobi was given Kigulu, Tabingwa was to oversee Luuka, and the youngest, Kitimbo, was to settle in Bugabula.

These allotted areas of supervision to the prince’s sons would later become major administrative areas and centres of cultural authority in Busoga. As anyone would expect, these princes employed the governing methods, setups, and cultural rituals they were familiar with, i.e., those of the Bunyoro-Kitara Kingdom.

These political and cultural administration arrangements continued until the late 19th century when the colonial intentions turned all the chiefdoms of Busoga into some form of a federation. This federation resulted in a regional Busoga council called Busoga Lukiiko.

Origin of the Name

It is believed in some circles that Byaruhanga coined the name “Busoga”. It’s said that the name was derived from a certain type of tree he found, one that can be seen everywhere in that area. In the native Lusoga language, it was called, and is still called, “omukakale” but in the Runyoro language, it was, and is still called, “Kisogasoga”.

Another oral tradition states that the name “Busoga” originated from a Basoga’s fighting technique. In the numerous wars of conquest that the Baganda engaged in with Busoga, the Basoga soldiers had a spearing technique that involved facing the spear downward while mutilating their enemy. In Lusoga, this kind of spearing technique was called “okusonga” but the Baganda called it “okusogga”. The Baganda, therefore, referred to their opponents as “abasogga”. Over time, the description solidified into a name: “Basoga”.

Meanwhile, some of the earliest writers about Busoga, like Fallers Lyolld (1965) and David William Cohen (1972), noted: “[T]he name ‘Busoga’ was originally used to refer to a hill located in the south-central part of the country and later it became identified with a state known as ‘Busoga’. This state was in the south-west of Jinja and was ruled by the lineage of Ntembe, of the Reedbuck clan.”

POLITICAL ORGANIZATION

Political Setting of Busoga: Cultural and Central Governance

POLITICAL HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

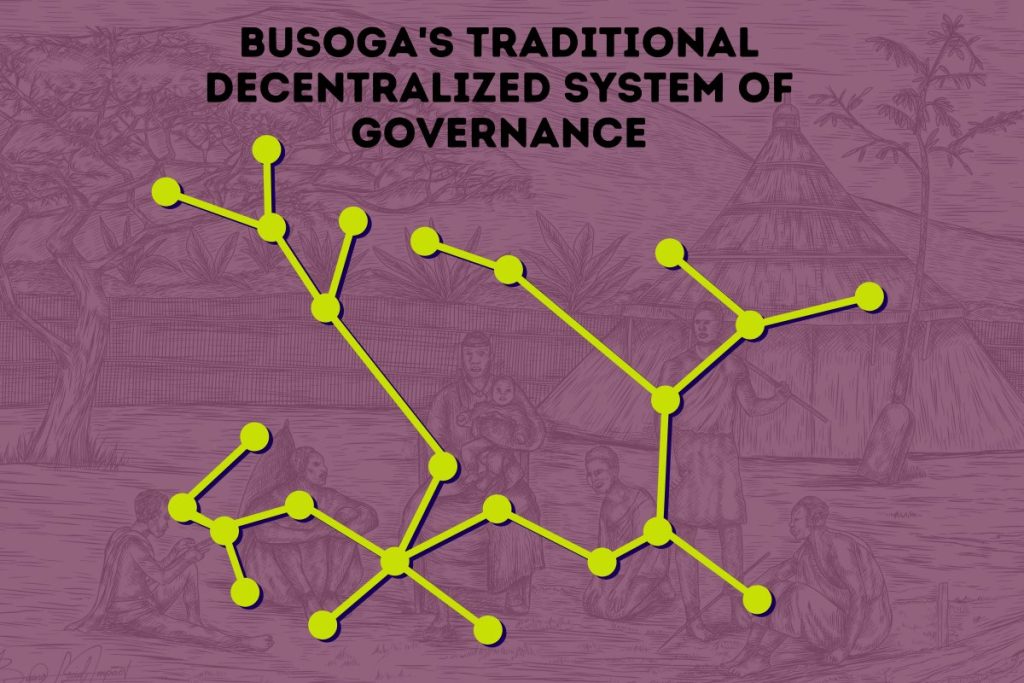

Pre-colonial Busoga was arranged in chiefdoms and stayed that way even under all “foreign” influences. You could say it was a semi-autonomous decentralised system of governance.

Unlike its neighbours, Busoga was not built on a diamond-shaped framework of administration, with an “all-powerful” authority figurehead (king or queen) at the top of a government – a kingdom.

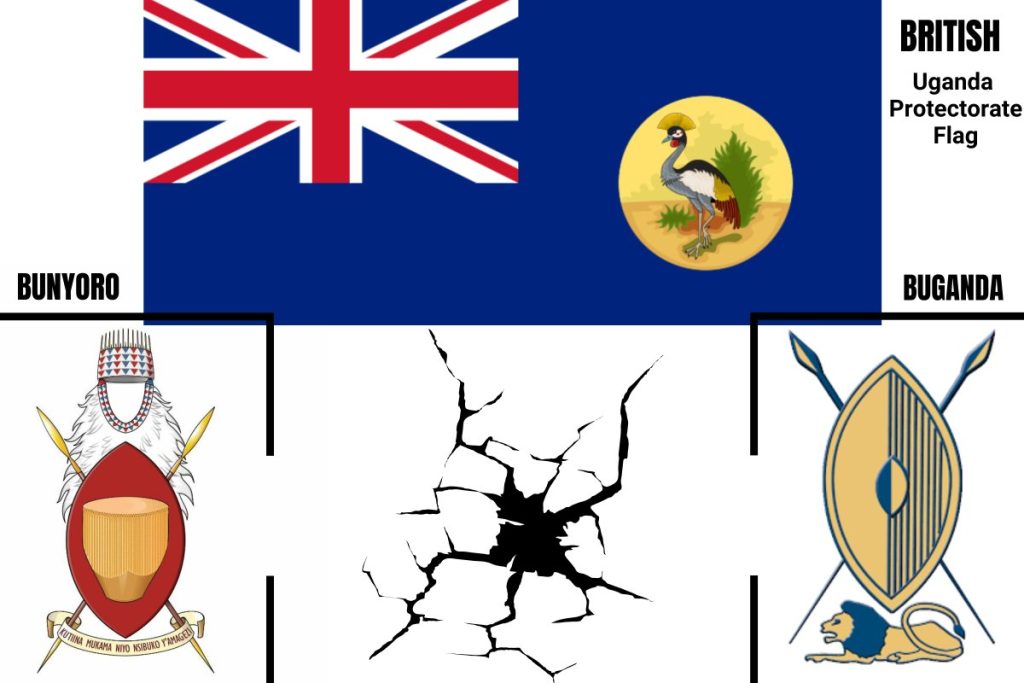

Not until 1906, at the behest of the British colonial powers, was the unification of these chiefdoms coordinated to create a kingdom.

The unification process started in 1906 with the establishment of an overall administrator known as the “President of Busoga Lukiiko” (Council). This title was changed in 1939 to “Isebantu Kyabazinga” (the father of the people who unites them). The new title gave Busoga a new identity.

One wouldn’t be off the mark to assume that the recent historical administrative construction of the Busoga Kingdom is a stimulus of the political influence of mainly the three foreign actors: Bunyoro, Buganda, and the British. At one time, these three colonial enforcements concomitantly ruled over Busoga, each with its primary and secondary interests. At the same time, the representatives of these colonial forces had personal or individual interests that differed from those of the respective institutions they represented.

From this point, Busoga’s social-economic stratum was ill-fated.

These new changes not only positioned Busoga in a vulnerable and negative framework but also laid it wide open as easy prey for manipulation.

Busoga found itself in an underdog position that still haunts the region today. Given that modern politics is the single most elevated sector dictating the shape society takes, through controlling resources and planning, surely Busoga must think anew.

However, the memory of the original chiefdom setup is still acknowledged today and there is an endeavour to keep it alive.